The Princeton roots of New Urbanism

An interesting piece in the Princeton Alumni Weekly outlines educational roots of New Urbanism founders and early leaders, and it turns out that Princeton University played a significant role. Four of the six architectural founders (Peter Katz, a nonarchitect who was the first Executive Director of CNU, could also be called a founder), plus some early leaders, were trained there. As the publication reports (including graduation dates—asterisk means post-graduate studies):

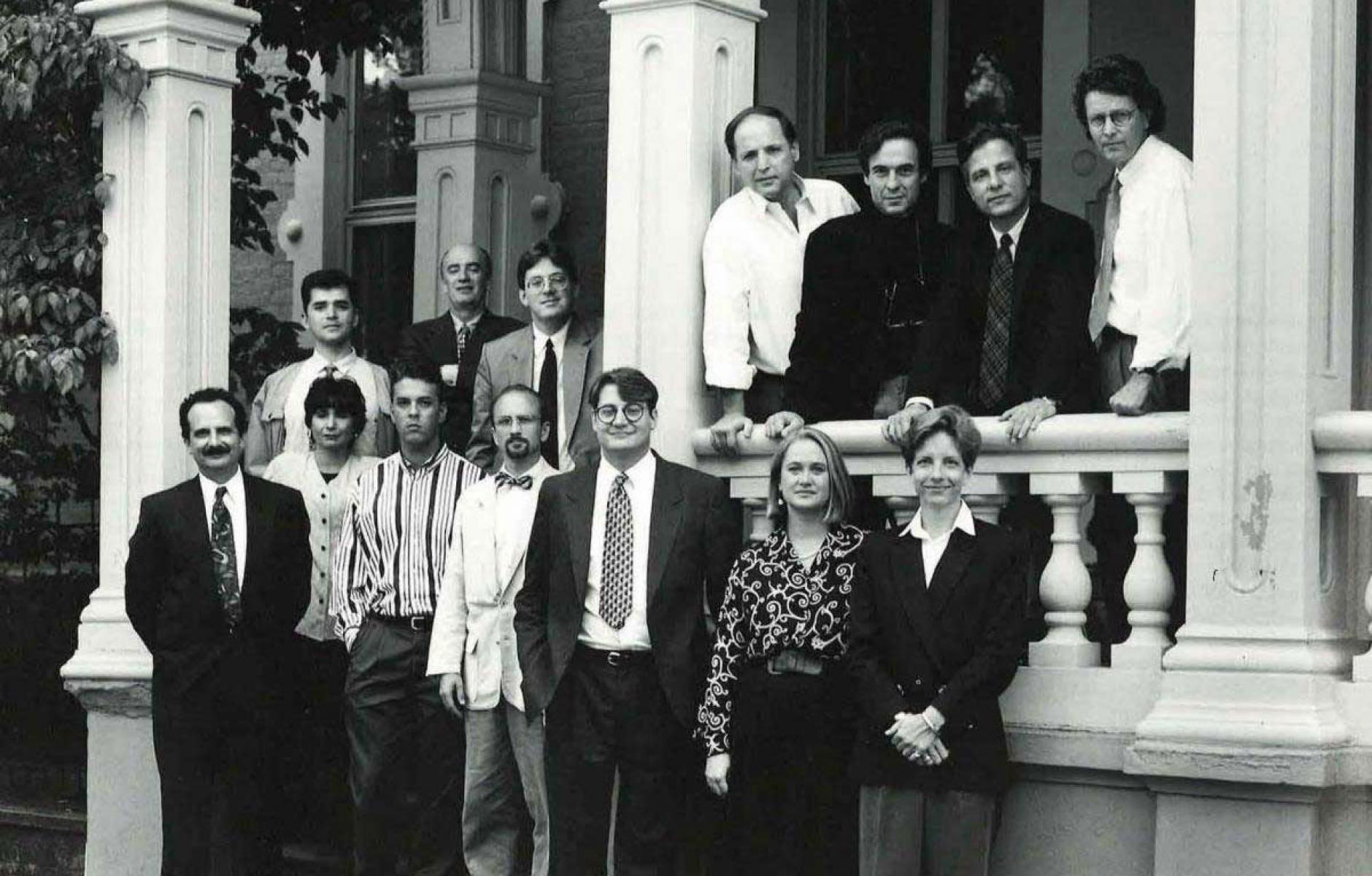

New Urbanism’s founders included the husband-and-wife team of Andres Duany ’71 and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk ’72 — as well as Elizabeth Moule *87 and Stefanos Polyzoides ’69 *72, who are also married. (The others are the Yale-taught Peter Calthorpe, and Daniel Solomon, trained at Columbia and Berkeley.) The founders recruited several more Princeton alumni to became early leaders of the movement. These include environmentalist and architect Douglas Kelbaugh ’67 *72, landscape architect Douglas Duany ’75, and writer and educator Ellen Dunham-Jones ’80 *83.

Yale can also boast outsized influence, as Duany and Plater-Zyberk received Master’s degrees there—which, in addition to Calthorpe, places half of the founders in New Haven, Connecticut. At Yale, architectural historian Vincent Scully was a legend, and his lectures influenced a generation of urbanists.

But what was in the air at Princeton? There were no true urbanists on the faculty—for example, teaching an approach to architecture that would lead to walkable cities and towns. It was more a general openness to new ideas—a kind of renaissance thinking that led early new urbanists on the path that would change the shape of the built environment. Here’s an excerpt:

After years of fealty to High Modernist theory, architects in the 1970s and ’80s were looking beyond the tenets of “form follows function,” and reexamining more historical forms and decorations. “For a brief window, Post-Modern and Modern were in a kind of equivalence. This was a moment when everything was on the table. It was a very short period of extreme open-mindedness, a unique educational experience,” Duany says.

This new openness to historical forms was in large part spurred by Princeton faculty member Michael Graves. Graves had begun his career as a staunch Modernist, but in 1959 he won the prestigious Rome Prize, which came with two years’ residency at the American Academy in the Ancient City. When that ended, Graves began teaching at Princeton.

“The lessons of Rome are the lessons of public space, of framed quads and courtyards and patios and streets, in symmetrical and asymmetrical configurations,” Polyzoides explains. “Through this, you discover the space of the city, within and beyond city blocks. That [spatial sense] is one of the key ingredients for the regeneration of the 21st-century city. And Michael was crucial in showing the way toward that.”

He continues: “The faculty was mostly Modernists, but what happened is they taught us how to read and write, and we went deeper than they thought we would. When I was Graves’ teaching assistant, I was pulling books from the library for him — books on French theory, the Ecole Des Beaux Arts — that hadn’t been checked out since the 1920s.”

The school’s dean, Robert Geddes, made sure that the program made full use of Princeton’s art history scholars. “Princeton’s history faculty was full of giants,” Polyzoides says. It included the archaeologist Richard Stillwell ’21 *24, who discovered the ancient city of Palmyra, as well as David Coffin ’40 *54, the world’s leading expert on Italian Renaissance landscape design. “While we were being fed stupid Modernist theory — the importance of building freeways, and the like — these people were talking about the root causes of architecture, with examples that were breathtaking: Renaissance palazzi, Greek temples, medieval cities.”

At the same time, the upheaval of the Vietnam War had given rise to a new social consciousness. “We set up a people’s workshop in New Brunswick, working with people directly on [design] projects,” Polyzoides recalls, “There was a clear understanding of the social dimensions of architecture at that time, almost on the level of what’s happening today.”

Thanks to CNU co-founder Elizabeth Moule for pointing me to this article.