A strong case for faster trains serving ‘megaregions’

Note: Many urbanists have time for reading as they hunker down in response to COVID-19, and there are excellent books coming out. We will be posting reviews on Public Square in the coming weeks.

Jonathan Barnett, winner of CNU’s prestigious Athena Medal in 2007 for his early influence on New Urbanism, has written Designing the Megaregion: Meeting Urban Challenges at a New Scale—a book that covers new ground. An architect, planner, and educator, Barnett brings design thinking of New Urbanism to “megaregions” that exceed the largest scale of the Charter of the New Urbanism.

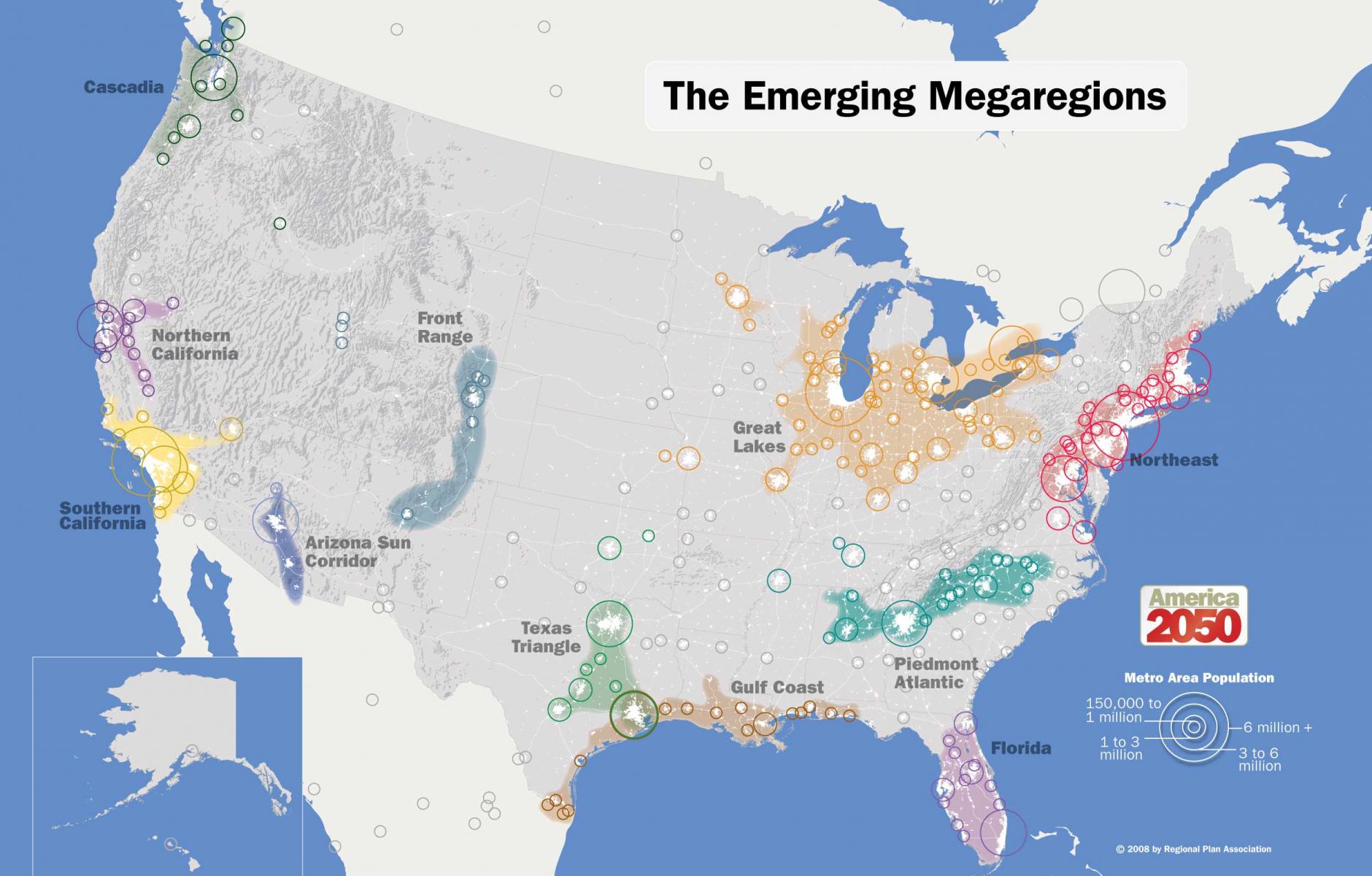

There are 11 emerging megaregions in the US, including the Northeast, the Great Lakes, Piedmont Atlantic, the Florida peninsula, the Gulf Coast, the Texas Triangle, the Front Range of the Rockies, Arizona Sun corridor, Southern California, Northern California, and Cascadia (Pacific Northwest)—see map at top. Five of these regions dip into Canada and Mexico.

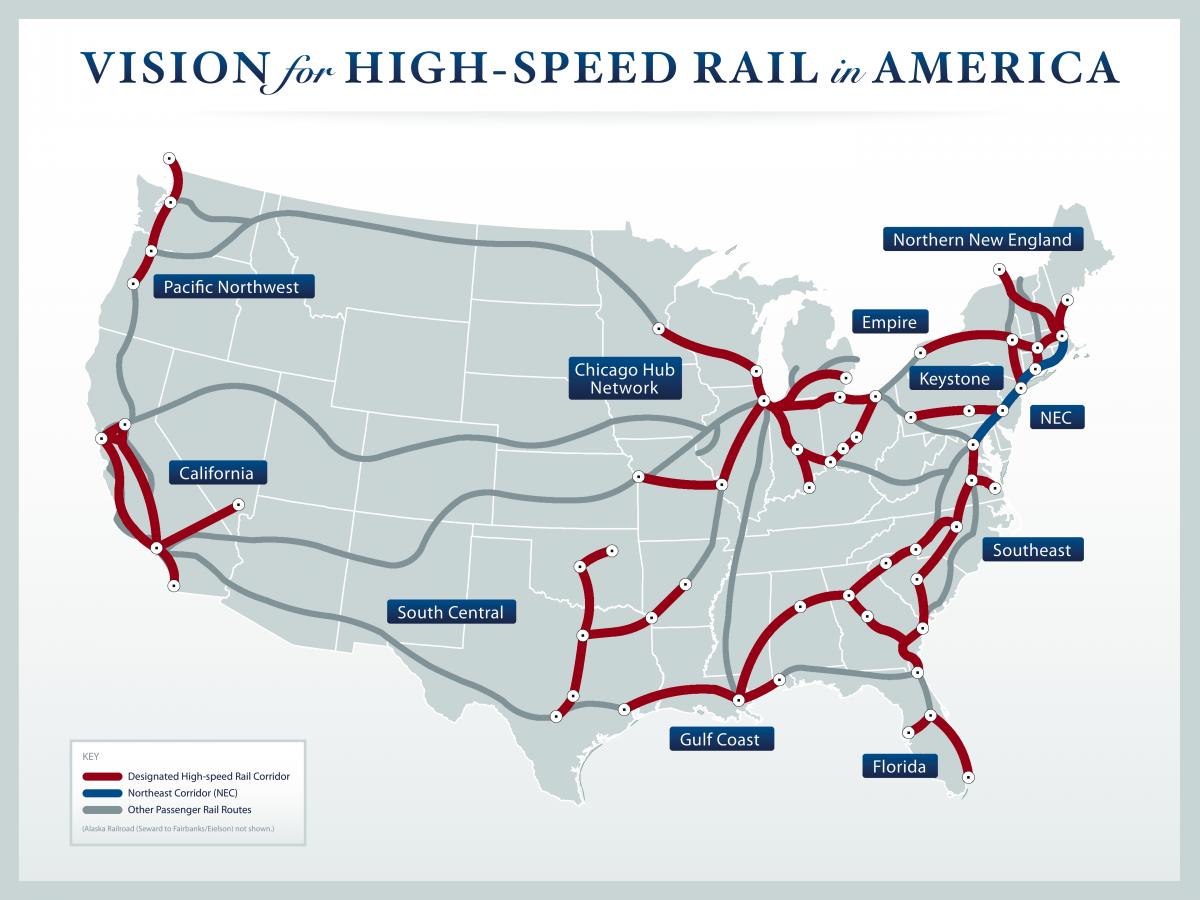

Barnett covers many topics, but intercity trains are the most interesting and relevant. He is not a big advocate of high-speed rail, which is very expensive, rather he argues for “fast enough” service—using existing technology like Acela in the northeast corridor. Such trains offer competitive alternatives to air travel and driving in megaregions.

The Northeast megaregion—which extends from Portland, Maine, to Richmond, Virginia—is the only one that comes close to offering the balanced transportation systems available in Europe, Barnett writes. Train service is a critical part of that balance. Amtrak’s Acela express takes just under three hours from New York to Washington, DC, and it has captured more than three-quarters of the passengers who might otherwise fly that route. Similarly, the Acela from New York to Boston takes four hours and has captured half of the air travel. “While it is not high-speed rail, is it fast-enough rail,” Barnett explains.

Acela provides a model for how rail can relieve growth pressures in airports and improve finances for trains. Because of the time it takes to travel to and through airports, trains don’t need to be high speed to be competitive—but they do need to improve service over what is available on most of Amtrak’s lines. “Trains that can attain 110 miles per hour and can operate at average speeds of 70 mph are fast enough to help balance transportation in megaregions,” Barnett says. Catenary electric trains, like the Acela, have maximum operating speeds of 150 mph, but only a few sections of track permit these speeds, he says. Currently, most Amtrak trains are powered by diesel locomotives with a maximum permitted speed of 79 mph and average operating speeds of 30 to 50 mph, Barnett writes. That’s too slow to compete with driving—let alone flying.

Technology that falls short of high-speed rail in Europe and Asia—which run at between 150 and 220 mph—could nevertheless be a game changer in many megaregions. “Using conventional technology like the Acela for rail service from Birmingham, Alabama, to Atlanta, Georgia—for example—would cut the main trip from more than four hours to less than two,” he writes.

He questions whether going all the way to high-speed rail, which is politically sexy and alluring, may be a mistake. California’s high-speed rail, which is planned to connect Los Angeles and the Bay Area—two megaregions—is expected to top $100 billion. The state only has funds for the middle section, which largely goes through agricultural land. “In retrospect, the $30 billion expended on the central segment could have gone a long way toward funding fast-enough trains, like the Acela, on Amtrak routes within the Bay Area and Los Angeles megaregions,” Barnett says.

Barnett is optimistic that “fast enough” rail travel in megaregions could be profitable for private investors like Virgin Trains USA, which is building an Acela-like train in Florida. “Today, for the first time in many years, there are private investors who are prepared to build and fund passenger rail transit—if the travel time, using the best available technology, is not more than two to three hours between key cities, and the cities are within megaregions,” says Barnett.

Developing station areas could help to fund improvements in service. Amtrak is already beginning to take advantage of major development opportunities, such as a planned 18 million square feet of mixed-use development on 175 acres over a rail yard near 30th Street Station in Philadelphia.

Climate change and sustainability

Barnett makes an argument for looking at the megaregion scale in preserving natural areas and planning for sustainability. This approach is often taken at a local and regional scale, but many natural features like watersheds impact multiple regions. “The watershed can be considered the equivalent of a design that needs to be preserved, in the same sense that a district of historic buildings forms an urban context that should be preserved,” he says.

Similarly, a changing climate affects the wildland-urban interface and the likelihood of fires that can destroy communities like Paradise, California. Barnett argues that hotter temperatures will make fires more of a threat in the East—especially since forests have reestablished themselves around and in cities.

Even suburban retrofit, zoning, and affordable housing are megaregional issues, he writes. Night sky satellite images show multistate commercial corridors like Route 1 between New York City to Boston. “The commercial corridor is becoming a land bank because of the revolution going on in retail,” he writes. Route 1, and many other similar commercial corridors dating from the middle of the 20th Century, could be redeveloped with high-density mixed-use including substantial affordable housing.

Political structures of megaregions often don’t allow for efficient planning decisions. Five of the 12 megaregions are located within single states, and this helps, Barnett says. “Where a megaregion is entirely within one state, there can be an alliance of MPOs, such as the Florida Metropolitan Planning Organization Advisory Council, which covers almost the whole state.” Where megaregions extend across state lines, an interstate compact is needed.

The growth of megaregions is inevitable through 2050 as America continues to urbanize, says Barnett. As this occurs, new development needs management to deal with climate change, better connections would benefit transportation systems, and inequality should be addressed, Barnett says. “Resolving these three sets of problems will produce designs for evolving megaregions that make them more sustainable, functional, and equitable.”

Designing the Megaregion offers a fresh perspective to issues that urbanists face day to day, such as transportation, housing, zoning, and planning for nature and resilience. I highly recommend it.

Designing the Megaregion: Meeting Urban Challenges at a New Scale. Island Press, 2020. 170 pp. $30.

Corrections: The original version of this review identified Acela trains as "third-rail trains," an error based on a misreading of the book text. As many readers pointed out, they use catenary power. The caption of the satellite photo mislabeled Hartfort, CT, as Boston, MA.