Using urban revival to reduce poverty

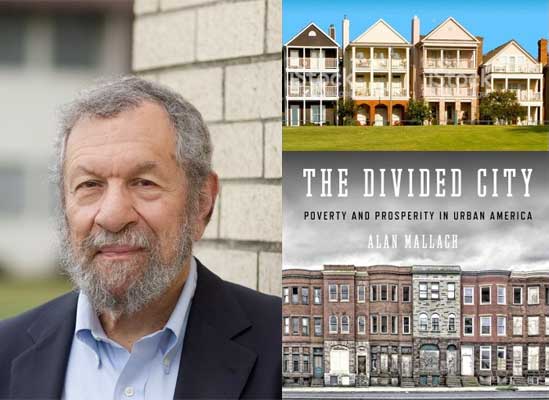

Note: This article is part of a collaboration between Island Press and Public Square that focuses on recently published books on subjects related to urbanism. Katharine Sucher of Island Press interviews The Divided City author Alan Mallach (questions in boldface).

You’ve been working in cities most of your life. What prompted you to write this book?

I think there’s an amazing and terribly important story to tell about what’s happening in America’s older cities, and I didn’t see anybody trying to tell it. Yes, there are books written from 30,000 feet about globalization and inequality, and there are some nitty-gritty neighborhood accounts, and they’re all important, but nobody’s looking both at the big picture and the reality on the ground in places like Baltimore, or Detroit. That’s what I’ve tried to do.

And what is that reality?

It’s two things. First, these cities are seeing a level of revival that thirty or forty years ago nobody would have believed possible. People moving in, new developments, new businesses, neighborhoods changing—it’s amazing. Second, for large parts of these same cities, things are getting worse. Poverty is increasing, and thousands of people are trapped in high-poverty ghettos with little hope and less opportunity. Figuring out how to bridge that divide is the challenge facing us.

Do the lessons in The Divided City apply to other, non-industrial cities? To suburbs?

Yes. The divide may well be the central reality of 21st Century America. You see it in the suburbs of places like Chicago or St. Louis as well. Suburbs are no long about the middle-class. There are a lot of suburbs—most of them built in the '50s and '60s—that are becoming high-poverty ghettos, and their future looks bleak. Things may be even worse in a lot of the small factory towns, like the ones along the Monongahela Valley in Pennsylvania.

Is gentrification a big issue in the cities you write about?

To listen to people talk, you might think so, but when you look at what’s going on, you find (if we’re talking about neighborhoods where a lot of affluent people are moving in and prices are skyrocketing) that there’s not really that much of it actually happening. Usually, a couple of small pockets near downtown, and little more. Gentrification has become a code word—many people use it because they are upset about the changes they see happening in their city, and angry about their lack of power to do anything about it.

What is a bigger issue?

The bigger issue that people aren’t talking about is that a lot more neighborhoods are falling behind and falling apart than are gentrifying. Neighborhoods that were pretty sound middle-class or working-class areas only 10 or 20 years ago are turning into high-poverty ghettos, the sort of neighborhoods where people walking away from houses they own because they’re not worth anything anymore. In most of the cities I looked at, for every neighborhood that was moving up or gentrifying, five, ten, or fifteen were sliding downhill. And what that means is that an entire generation of homeowners—many, maybe most of them, African-American—are seeing whatever wealth they have, which is tied up in their homes, disappear.

Universities and hospitals—“eds and meds”—are driving growth in a lot of cities. Yes, they are drawing new, educated young people to the cities, but what opportunities do they offer long-term city residents—particularly low-income residents?

Potentially, a lot. These institutions are job machines. The University of Pittsburgh Medical Center employs over 50,000 people and is the largest private employer in the state of Pennsylvania. Most of their jobs aren’t for people with MDs or PhDs—most of them don’t even require a college degree. We need a system that would educate or train the people who live in these cities for those jobs. There are people doing this around the country, but on a terribly small scale. If we could only get everyone together we could come up with a way to make it work for thousands of people, not dozens.

What is the key to sustaining urban revival in older industrial cities?

Urban revival is happening. It’s new, it’s fragile, and it happened without any real leadership from city government or anyone else. But it gives places like Philadelphia and St. Louis a powerful tailwind. What cities now have to do is systematically build on it. They need to be diversifying their economies beyond the core eds and meds, the way Pittsburgh is doing with robotics, or St. Louis with biomedical research. They need to be working harder to make their cities attractive not just to young people who like the downtown scene, but to families with children, empty nesters, and older people.

But there are two more things that may be even more important. First, successful cities need to do a better job building the human capital of the people who live there already; and second, city governments need to do a better job governing and connecting to the people who make up the city. Judging from the conversations I’ve had with a lot of people over the past few years, almost all of them feel their city doesn’t care about them, and as far as I can tell, they’re usually right.

You profile a number of city governments, nonprofit entities, and citizens working on the ground to address challenges of change in industrial cities. Does a particular story or project stand out to you?

Two, actually. In Minneapolis, first Steven Rothschild and now Tom Streitz have created an organization called Twin Cities RISE! which has developed a program that has taken hundreds of the hardest to place people in the Twin Cities area, and trained and placed them in well-paying, stable jobs. They’ve learned that training is about a lot more than just learning job skills.

The second is the Youngstown Neighborhood Development Corporation, in Youngstown, Ohio, one of the most depressed cities in the United States. Under the leadership first of Presley Gillespie and now Ian Beniston, their mission is basically “whatever it takes.” They do an amazing range of things and have given hope to people and neighborhoods in a city that most people would have written off.

When you talk about equality and opportunity, what do you mean by that?

Equality is a funny word. People aren’t equal—some people are tall, some are short, some can play the violin, and so forth. To me the most important thing is that our society should offer every single man and woman the opportunity to succeed to the best of their ability. And at its most basic, opportunity begins with three things: people should be able to get a decent, stable job; their children should be able to get an education that allows them to succeed; and they should be able to live in decent housing in a safe, healthy neighborhood. And there are millions of people in this county—poor and near-poor, disproportionately people of color —who don’t have any of those three things. It may sound pretty prosaic, but I truly believe that that’s what it’s really about.

You write that changing the situation is basically a local, not a federal issue. Why is that?

Ultimately, whether people have access to job opportunities, their kids get a decent education, or their neighborhoods become healthier, safer places to live is the result of decisions made locally, collectively by the people who make up the local power coalition, and whoever can bring their influence to bear on that coalition. In the end, creating greater equality and opportunity is about changing their agenda, and there’s nothing the federal government can do to force them to do it.

Money is important, but it’s not really about money. Since the 1990s, the state of Ohio, Cuyahoga County and the city of Cleveland have spent about $800 million in today’s dollars to build two sports stadiums and an arena. And I’m sure it’s great to see LeBron James play for the Cavaliers in that arena. But it would have taken only a fraction of that amount to train and place every unemployed man and woman in Cleveland in a good, stable job.

Is there anything that the federal government should be doing?

One big thing. Perhaps the single biggest thing thwarting the hopes of poor people in this country —particularly single mothers and their children—is the fact that, except for the lucky few that get a voucher or an apartment in a subsidized development, they have to spend 50 percent, 60 percent, or even more of their income on rent. And that means that they are constantly falling behind, constantly being evicted, doubling up, becoming homeless, and their children are moving from school to school, and steadily falling behind.

We help people in the United States with health care through Medicaid, and with food with the SNAP program. They’re not great, but they provide a floor for people. But, except for a lucky few, we tell the same people that they’re on their own when it comes to finding a place to live. And only the federal government has the deep pockets to solve this problem.

There are a lot of other things the federal government can do in the way of changing programs and regulations, and by how they set the tone for urban policy, but in the end, all of that won’t make a lot of difference unless people do the heavy lifting city by city, metro by metro.

Did you learn anything in the course of researching and writing The Divided City that surprised you?

Most of my training and background has had to do with the physical side of cities—land, properties, housing developments, that sort of thing—and I knew a lot about what was going on in that area. So, when I began researching The Divided City I didn’t know as much as I could have about what the issues were, and what people were doing around education, training, jobs—the human side of the equation.

What I learned was that we know how to do stuff. We know how to move high school dropouts and ex-offenders into good jobs. We know how to take inner-city kids from poor households and enable them not only to get into college, but to graduate. So for me, the big question became, not how do we do it, but why don’t we do it? What’s keeping us from taking what we know, and applying to the millions of adults and kids who need it?

What do you hope readers take away from this book?

Concentrated poverty, polarization, exclusion, lack of opportunity—none of these are forces of nature. They’re the result of decisions, and they can be changed. And in this country, we have the skills and the money to change them. The question is, do we have the will?