The real ‘Bilbao Effect’

Note: This article is part of a collaboration between Island Press and Public Square on a series of articles based on recently published books on subjects related to urbanism.

The question 'What makes a great city?' is not about the most beautiful, convenient, or well-managed city; it isn’t even about any “city.” For me it is about what we can do to make a city great. To my surprise I found the answer in Bilbao, Spain. I was familiar with the “Bilbao Effect,” in which the opening of a branch of the Guggenheim Museum, I had been told, reversed years of economic decline and transformed Bilbao into an urban celebrity. To be fair from the outset, I thought that the notion that showpiece attractions, like the Bilbao Guggenheim, could by themselves make a city great was highly unlikely, but not impossible. After all, when people think of London, they remember St. Paul’s Cathedral, Westminster, and London Bridge, just as they recall the Statue of Liberty, Times Square, and the United Nations when they think of New York. Identifying a city with its special attractions is a widespread phenomenon, but ascribing that city’s greatness to the presence of one special attraction seemed to me a bit of a stretch.

I became aware of Bilbao thirty years ago when the city had become a well-known economic basket case. At that time, there was no reason for me to go there. That reason came later with the opening of a branch of the Guggenheim Museum in 1997. I wanted to see Frank Gehry’s extraordinary new building, so in 2013, I traveled to Bilbao to discover what had happened and to learn why. When I arrived in Bilbao, I found a thriving metropolis whose residents had little involvement with the Guggenheim Museum. They jammed stores and restaurants. Children, parents, and dog walkers filled the parks. Unlike me, they were not visitors who had come to see the Guggenheim. Certainly, the museum had enhanced the life of the city, made Bilbao a tourist destination, and generated substantial additional economic activity. How, I wondered, could a museum solve fundamental economic problems?

As I soon discovered, the museum alone had not transformed the city. Bilbao’s transformation was the product of major investments in environmental decontamination, flood protection, and riverfront redevelopment, as well as its significant expansion of the public transportation system, and perhaps most important, major improvements to its streets, squares, and parks. Indeed, collectively, these initiatives were the reason that the city was full of satisfied shoppers, ordinary grandmothers, international business leaders, curious teenagers, talented workers, and everybody else.

When the municipality of Bilbao reached its peak population of 433,000 in 1980, it was famous for the filthy buildings and foul air “from the blast furnaces along a stinking river that trafficked in floating objects,” as The New York Times reported. At that time, the city’s industrial base (steel, machine engineering, and shipyards) was already in decline. Unemployment was close to 25 percent. Between 1975 and 1995, Bilbao lost 60,000 industrial jobs, cutting industrial employment in half. The accompanying flight of population from Bilbao resulted in a population decline of 81,000 people (19 percent) by 2010.

Disaster hit on August 26, 1983, when the Nervión River, which runs through Bilbao, flooded, rising as much as ten feet. The flooding caused parts of two bridges to collapse and resulted in the death of 37 people in that region of Spain. Local, regional, and national leaders responded to the crisis with a program that dramatized the devastation caused by flooding as a way of galvanizing public support for actions that addressed fundamental economic and environmental problems.

The redevelopment program that emerged over the next eight years included:

• eliminating pollution from the Nervión River;

• decontaminating and physically reconstructing large areas of land along the river;

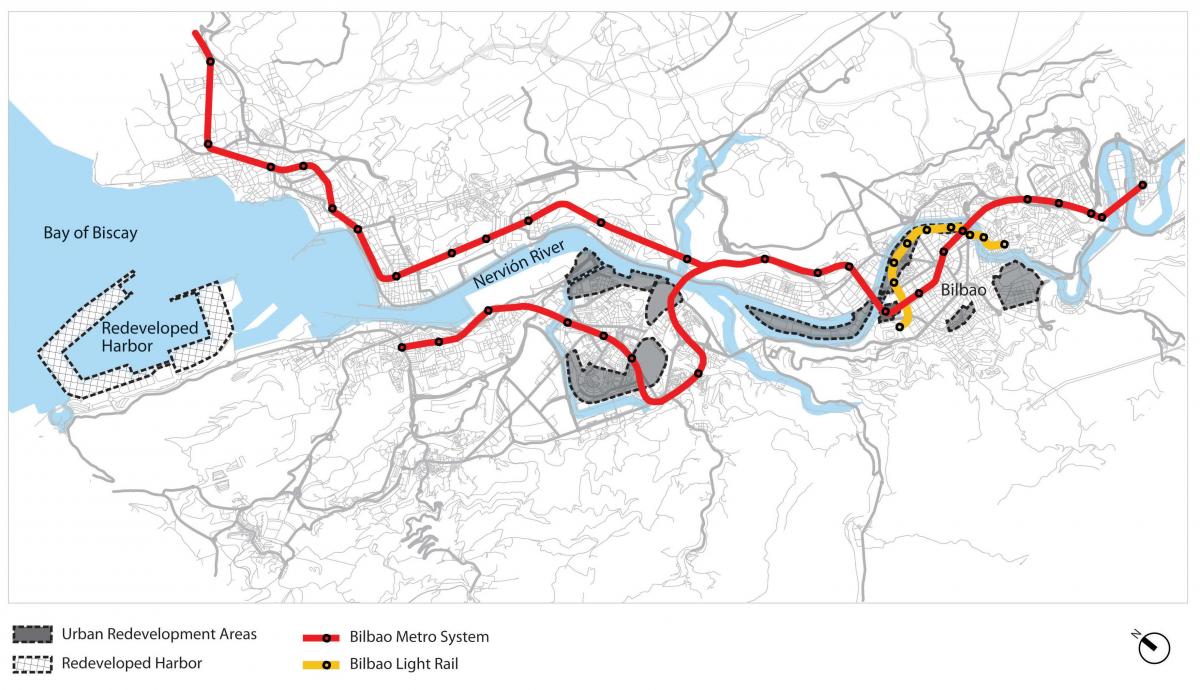

• expanding port facilities at the mouth of the river in the Bay of Biscay, relocating shipping activity from the river to the bay, and redeveloping riverfront property previously used for shipping or manufacturing;

• investing in public transportation that included Metro, a new underground system that connects the communities along the river with those along the bay, restructuring and expanding the existing urban railway, creating a light rail system connecting in-town neighborhoods, and interconnecting all of them;

• creating a 4.7-mile (7.5-km) riverfront promenade.

These actions were embodied in the Strategic Plan for the Revitalization of Metropolitan Bilbao that was agreed to in 1991. They would be promoted and implemented by two agencies created with the specific purpose of carrying out the plan: Bilbao Ría 2000 and Bilbao Metrópoli-30.

Long before the strategic plan was officially adopted, government agencies had decided to invest in the subway system and began assembling properties and decontaminating sites that had redevelopment potential. In 1988 the British architect Norman Foster won a competition for the design of the Metro.

The Guggenheim arrives

Three years after Foster began work on the Metro, when an art exhibition from the Guggenheim opened at the Reina Sophia Museum in Madrid, the Bank of Bilbao was persuaded to finance a successful effort to convince the Guggenheim Museum to open a branch in Bilbao. It took the leaders of Bilbao another two years to convince the Guggenheim to accept the offer of a site along the Nervión River that was in one of several redevelopment areas.

The new museum was designed by the American architect Frank Gehry. And when it opened in 1997, the Bilbao Guggenheim became the instant icon of the city’s revitalization—a beacon announcing its importance to the rest of the world. The spectacular building that Gehry designed made him the most famous American architect since Frank Lloyd Wright, and the publicity that the museum building generated transformed this relatively obscure provincial city (the tenth largest in Spain) into an internationally known tourist destination. It was natural, therefore, to believe that the museum was responsible for Bilbao’s revival.

The Bilbao where the Guggenheim Museum now stands bears little resemblance to the city that the Nervión flooded in 1983. In 1996, the year before the museum opened, 169,000 visitors came to Bilbao. Fifteen years later, the number had risen to 726,000, with some of the increase attributable to the opening of the Bilbao Exhibition Centre in 2004, which attracted an additional 100,000 convention participants. The city’s population had fallen from 433,000 in 1980, stabilizing in 2010 at just above 350,000. The metropolitan area gained 113,000 jobs between 1995 and 2005, according to a London School of Economics report. The unemployment rate dropped from 25 percent to 14 percent, four percentage points lower than that of Spain as a whole. Clearly the city had been doing something right, but it would be rash to ascribe such success solely to the opening of a major museum when the story is so much deeper.

Access to the riverfront via a beautiful promenade may be what visitors encounter as soon as they leave their hotel to go to the Guggenheim Museum, but those visitors are only a small portion of the people sitting on benches, or strolling, jogging, and cycling along the promenade. Residents flock to reconfigured and repaved downtown streets. In some areas, such as Calle Ercilla, the street has been re-landscaped, vehicular traffic prohibited, and the roadway reallocated entirely to pedestrians. Many public squares have been redesigned, and if there is a subway stop, such as at Plaza Moyua, outfitted with distinctive entrances to the Metro. Public parks have been updated to provide places for dog owners to congregate, children to play, older people to sit in the shade, and everybody to enjoy.

The riverfront promenade, street improvements, pedestrian precincts, reconceived public squares and parks, light rail and subway lines, and new public buildings were envisioned as ways of retrofitting Bilbao for the 21st Century. These public realm investments made the city easily accessible to tens of thousands of people for whom reaching the city and getting around in it had been difficult and expensive. Its streets, squares, parks, and once-contaminated sections of the waterfront were transformed into safe, well-maintained, friendly places that provide amenities for everybody, regardless of income, social standing, or proximity to the city center. In addition to making it more livable, this massive public investment throughout the city also transformed perceptions of the city. People began to think of Bilbao as a desirable place to live and do business. Many of them decided to expand existing businesses or open new ventures there. The Guggenheim was not what made the difference, rather the new public realm (of which the Guggenheim is now part) attracted and kept people and businesses in Bilbao. And these people are the ones who are making Bilbao one of the great cities of Spain.

My visit to Bilbao convinced me that people are what make a city great. The public realm may be what initially attracts them. But there comes a time when without adjustments it will no longer keep them there. So they make the changes they need, changes that attract others as well. What I learned in Bilbao underscored what I already believed: that a great city, unlike a great painting or sculpture, is not an exquisite, completed artifact.

This article was an excerpt from What Makes a Great City by Alexander Garvin. Copyright © 2016 Alexander Garvin. Reproduced by permission of Island Press, Washington, D.C.