Busting the myth that alleys cost more

One of the frequent complaints we hear from homebuilders – at least those who aren’t familiar with successful new urbanist development models – is that they “can’t afford alleys”, and that “alleys just double the number of streets”.

Indeed, perhaps the most commonly cited reason that national homebuilders give for dismissing New Urbanist planning is the perceived costs of alleyways in much of our planning. But as our analysis shows, this is a misconception. A more accurate understanding of the differential costs of alleys could be the key to convincing more of those homebuilders to the financial (and other) benefits of walkable communities served by mid-block alleys.

Of course, the cost barriers for alternatives to “business as usual development” are always issues to be taken seriously. However, based on our own experience, these common complaints just don’t hold water. After hearing this one too many times from local single-family builders on a number of our projects through the years, we decided to conduct a careful apples-to-apples analysis, working with the help of our colleague Paul Crabtree of Crabtree Group civil engineers. (Note that this analysis focuses on single-family homes, not multi-family.)

Some builders have other objections to alleys beyond cost, including the claims that “buyers don’t like them” and also that alleys increase crime, both of which are also disproven by the evidence – but we’ll come back to those issues later. First, we’ll look at the economics, since that’s usually the biggest hurdle.

Our analysis (available at https://www.michaelwmehaffy.com/alley-cost) concludes:

- Alley-loaded home developments need not cost more per lot than front-loaded ones, and in fact can cost considerably less, depending on the choice of lot dimensions and other factors.

- It is notable that the cost of alley paving per lot is largely offset by the area and cost of driveways on comparable front-loaded homes.

- Front-loaded homes on streets with on-street parking have a higher cost of street construction, owing to the wasted pavement area in front of the driveways (since it can’t be used for parking or for travel, even though it must be constructed to the same standard as the rest of the street). This has the effect of essentially doubling the cost per stall for on-street parking with front-loaded lots.

- In the case of small lots (under 4,000 SF), the infrastructure cost per lot for the narrower lots on alleys is significantly less than that for front-loaded lots with wide frontages – a lot shape that is generally required for homes with front-loaded garages – since the infrastructure cost is directly related to lot frontage length.

Let’s unpack the issues.

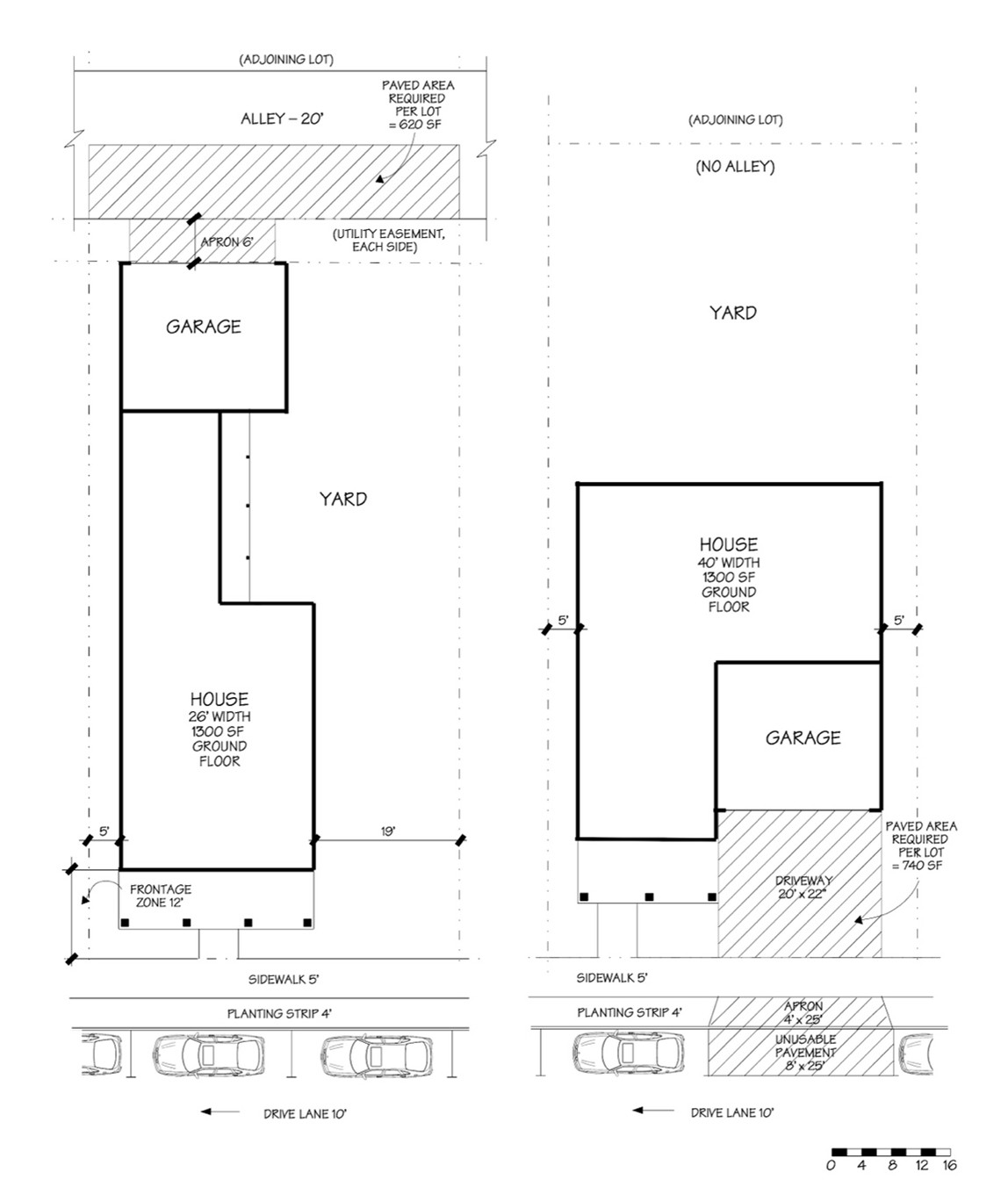

The amount and cost of paving an alley is similar to that for all the driveways in a comparably sized block. Consider two identically sized lots, 50 feet wide x 100 feet deep, each with single-family detached homes of 1,300 square feet each. (The analysis for attached homes would be similar, but we’ll focus on detached homes for this comparison.)

The paving area for the alley is 620 square feet, and for the driveway, it’s 740 square feet. The alley might well have a deeper thickness of concrete and sub-grade, raising the price – but you can see that the area is certainly similar.

But there’s another important diseconomy for the house on the right: the additional paved area includes a portion of the street itself, which is essentially wasted space and expense. In the lot on the left, that space can be used for on-street parking. But the builder or developer of the lot on the right still has to construct that wasted space to the full standard of the street.

Our analysis shows that, when all the development costs are calculated, the difference in cost between a front-loaded and rear-alley home is negligible – we got a value of 0.09% more expensive for the front-loaded house. This is for the same lot size and shape, 50 x 100 or 5,000 square feet.

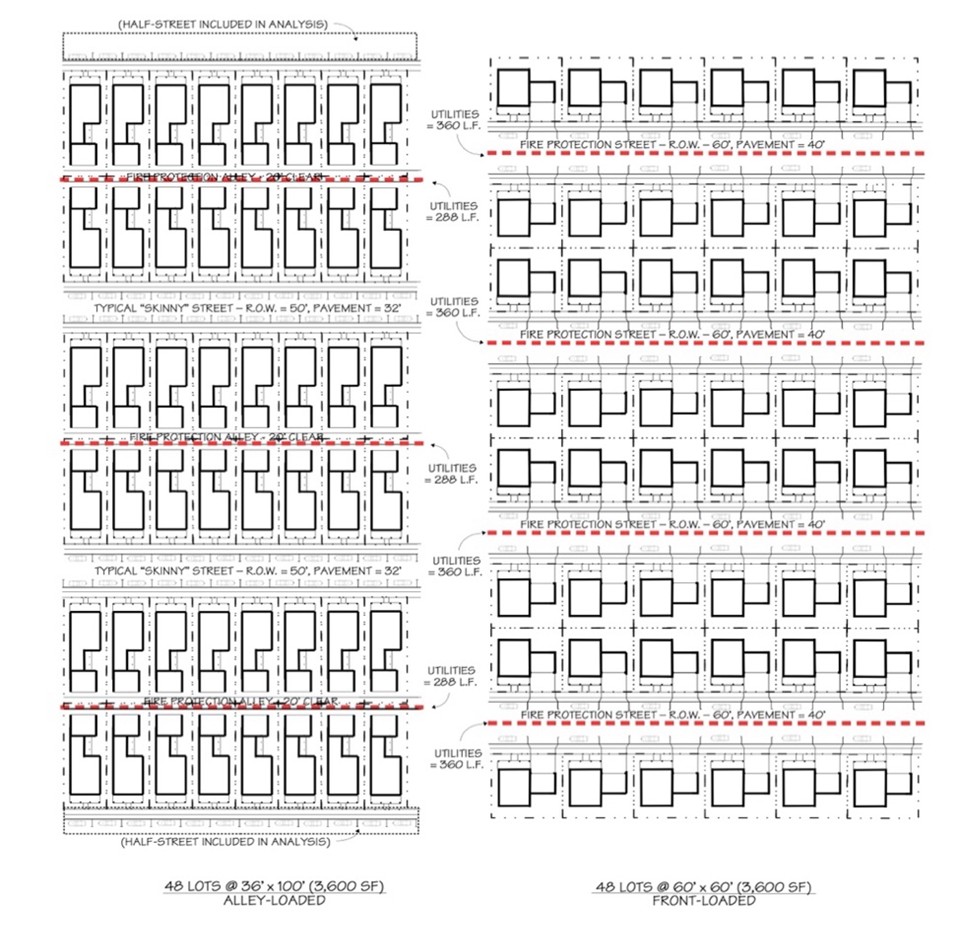

What happens when the shape of the lot changes – when, for example, the lots are long and skinny versus short and square, as many front-loaded suburban lots are? The difference in cost becomes much more dramatic: the front-loaded lots becomes even more expensively. When we compared 36’ wide x 100’ deep lots (3,600 square feet) to 60’ wide x 60’ deep lots (also 3,600 square feet) the front-loaded lots were 69% more expensive.

What accounts for this dramatic difference? The illustration below reveals the issue. The frequency of streets with expensive infrastructure (red lines) is significantly higher in the front-loaded neighborhood – four lines versus three in the alley-loaded neighborhood – translating into significantly higher infrastructure cost per lot.

There are ways of increasing the cost savings even more, including making skinnier streets – a common feature in alley-loaded neighborhoods, since fire protection is often accessed from the alleys.

An even more dramatic cost reduction can be done by removing the streets altogether and using greenways instead. These can include small lanes for cars, forming “shared space” zones or “woonerfs” (from the Dutch model). Or they can exclude cars altogether, and allow the alleys or lanes to serve all vehicular traffic (including fire and other emergency services). We have used this model, which we call a “laneway-greenway model”, on several projects. Below is an example from a forthcoming project in Ashland, Oregon, the redevelopment of a former timber mill.

But will buyers accept alley-loaded homes? Some builders are skeptical – yet the evidence is persuasive. Some typical data points:

- The sales in many New Urbanist developments where alleys are a defining design feature, alongside front porches, walkability, and a mix of uses, show consistent premiums: Kentlands (MD) ~15%, Southern Village (NC) ~10%, Laguna West (CA) ~4% over nearby comparable subdivisions with front-loaded homes.[1]

- A planning analysis from Montgomery County, MD, reports rear-loaded townhouses “command significantly higher prices” than front-loaded peers in their region.[2]

- A municipal housing market study (West Bloomfield, MI) documents buyer preference for developments with sidewalks and side- or rear-loaded garages, including alley access.[3]

A key issue is whether the homes maintain private outdoor space – either a back yard, or an adequately sized side yard. When homes on alleys lack this basic amenity, they are certainly at a competitive disadvantage compared to front-loaded homes with a back yard. But that’s true with or without alleys.

A second related point is that alleys need to be seen as part of a system, including walkable streets uninterrupted by garages and driveways, street-friendly architecture with appealing porches or stoops, a mix of uses and destinations, and paths and goals that make walking and biking appealing.

One last point: the claim that alleys by themselves increase crime is not supported by the evidence. As Hillier and Sahbaz (2008)[4] and others have shown, “eyes on the street” – or on the alley – promote safety. Well-designed alleys, with windows facing them and active use by pedestrians, bikes and cars, need not be any more likely to see criminal activity than any other street, lane or walkway.

Our takeaways for best practice:

Preserve usable private yard space (rear or side) while keeping garages on the lane.

Treat the alley as a mews: good lighting, frequent doors/windows, landscaping, and clear operations for trash/recycling—this shifts perceptions from “service alley” to “shared court.”

Market the streetscape benefits (porches, trees, fewer curb cuts) that correlate with premiums in the comparable sales.

This analysis reminds us that, like all components of the cost of development, the cost of alleys depends on a number of complex factors. However, the analysis also shows that it’s possible to not only avoid extra cost with alleys, but to save cost compared to conventional front-loaded development. The win-win result can be a much more walkable, more attractive, and ultimately more successful neighborhood.

[1] Tu, C. C., & Eppli, M. J. (2001). An empirical examination of traditional neighborhood development. Real Estate Economics, 29(3), 485-501.

[2] Paul Mortensen (2016). Garage Location Makes a Huge Difference in Community Livability. Montgomery County Planning Department. Available at https://montgomeryplanning.org/blog-design/2016/07/garage-location-makes...

[3] Township of West Bloomfield (2019). West Bloomfield, Michigan Housing Market Study. Available at https://cms4files1.revize.com/westbloomfieldtwp/document_center/PDS%20De...

[4] Hillier, B., & Sahbaz, O. (2008). An evidence based approach to crime and urban design, or, can we have vitality, sustainability and security all at once. London: Space Syntax.