Old versus New Urbanism, and what it means

A professor of real estate visited the Florida Panhandle and compared the New Urbanism on Route 30A (Seaside, Rosemary Beach, Alys Beach) to the “old urbanism” of Panama City, about 30 miles to the east. J. David Chapman, chair of finance and professor of real estate at The University of Central Oklahoma, explains that old urbanism is organic and New Urbanism is more intentional and curated.

In a report for Oklahoma City’s The Journal Record, he notes, “The difference, as I experienced it last week, is authenticity through time versus authenticity through design. Both have value. Panama City’s downtown is rebuilding from disaster, holding onto its history while slowly adapting to modern needs. I found myself envious of their new streetscape, the roundabout traffic system, and improved street lighting—though certainly not envious of the reason for the retrofit: the devastation caused by Hurricane Michael.”

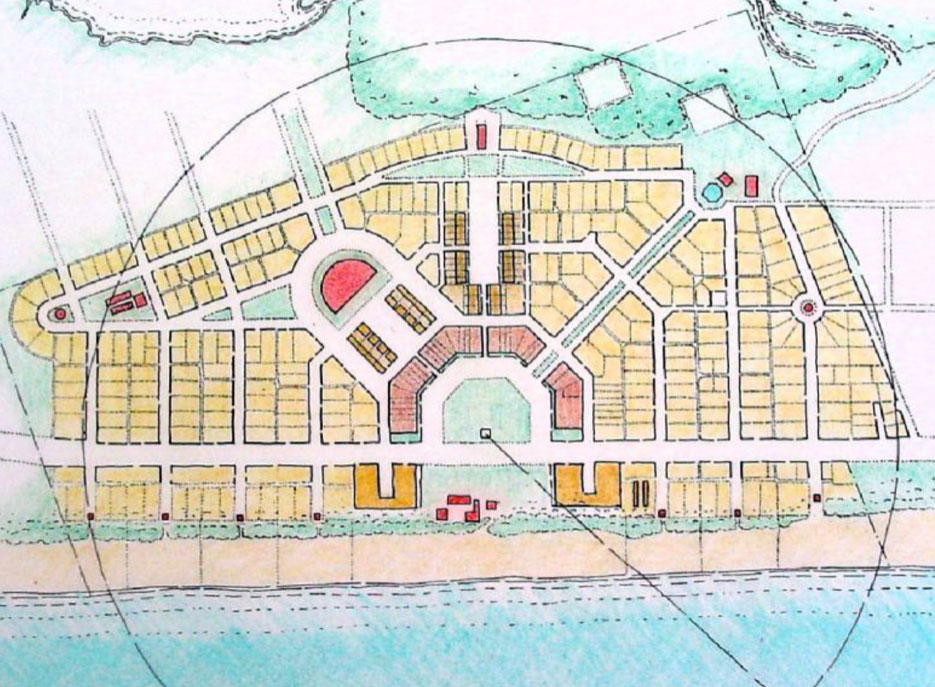

That’s fair, but Professor Chapman is missing an important point: The new streetscape and roundabout at the heart of Panama City comes from a new urbanist recovery plan for the city, which won a CNU Charter Award in 2020. The Strategic Vision for Panama City is New Urbanism, no less than Seaside. The distinction between old urbanism and New Urbanism is not as clear-cut as he supposes.

It’s true that before the widespread use of personal automobiles, urbanism was essentially the only game in town when it came to city building. Laying down a street grid was as natural as laying a foundation for a house. It happened in thousands of cities and towns, until it didn’t. That change abruptly occurred nationwide around 1950, after the Great Depression and World War II precluded significant changes in the built form for nearly two decades. Meanwhile, automobiles had become a fixture for American families since the 1920s, and planners and builders were hankering to implement new ideas that were considered modern and progressive at the time.

Depending on how you look at it, America had a half-century or more when walkable urbanism was deemed obsolete. There was little or no “New Urbanism” during that period. We only had historic urbanism, and that was often damaged by road widenings, highways, urban renewal, and careless planning and development. The mistakes made in the era when the idea of urbanism was abandoned have been widely discussed, especially on Public Square.

The point is that New Urbanism was the revival of urbanism after a prolonged period of absence. As Professor Chapman notes, New Urbanism was more intentional and self-conscious because it had to be. New urbanists had to recover ideas that had been discarded historically. In doing so, they could look back on centuries of urbanism for inspiration, and combine these ideas with new ones tailored to modern technology and markets. New urbanist design can be applied to new communities and neighborhoods, as well as to historic cities and towns. In Panama City, the tragedy of Hurricane Michael opened the door for revitalization of the city center, with the help of New Urbanism. It is safe to say that without New Urbanism, the redo of Panama City’s downtown would look far different.

New Urbanism responds to issues that didn’t exist or weren’t considered important when Panama City was incorporated in 1909. For example, the traffic calming that is emphasized in the recent streetscape and roundabout responds to the problems associated with an automobile-oriented society. As a low-lying coastal city, Panama City faces threats from climate change. The vision plan by Dover, Kohl & Associates takes a hard look at sea level rise, not shrinking from worst-case scenarios. The plan takes into account a potential 10-foot rise, which means the city will be better prepared in the decades to come.

Urbanism is alive and changing in Panama City, just as it is along 30A in Walton County.