Natural experiment: Walkable places boost physical activity

That people walk more in walkable places is clear. However, a debate has long persisted over the extent to which walkable cities cause that activity, or do they merely attract those who already want to walk? This is called “self-selection bias.” I’ve never really understood why this debate matters—if walkable places enable people who want to walk but were previously stymied by a poor physical environment, the effect is the same: more physical activity and better health.

I pay close attention to my daily steps. Whenever I go to a highly walkable city (from my home in a semi-walkable village), my steps double or triple. Going to a more walkable place doesn’t necessarily boost my motivation, but it supports my inclination.

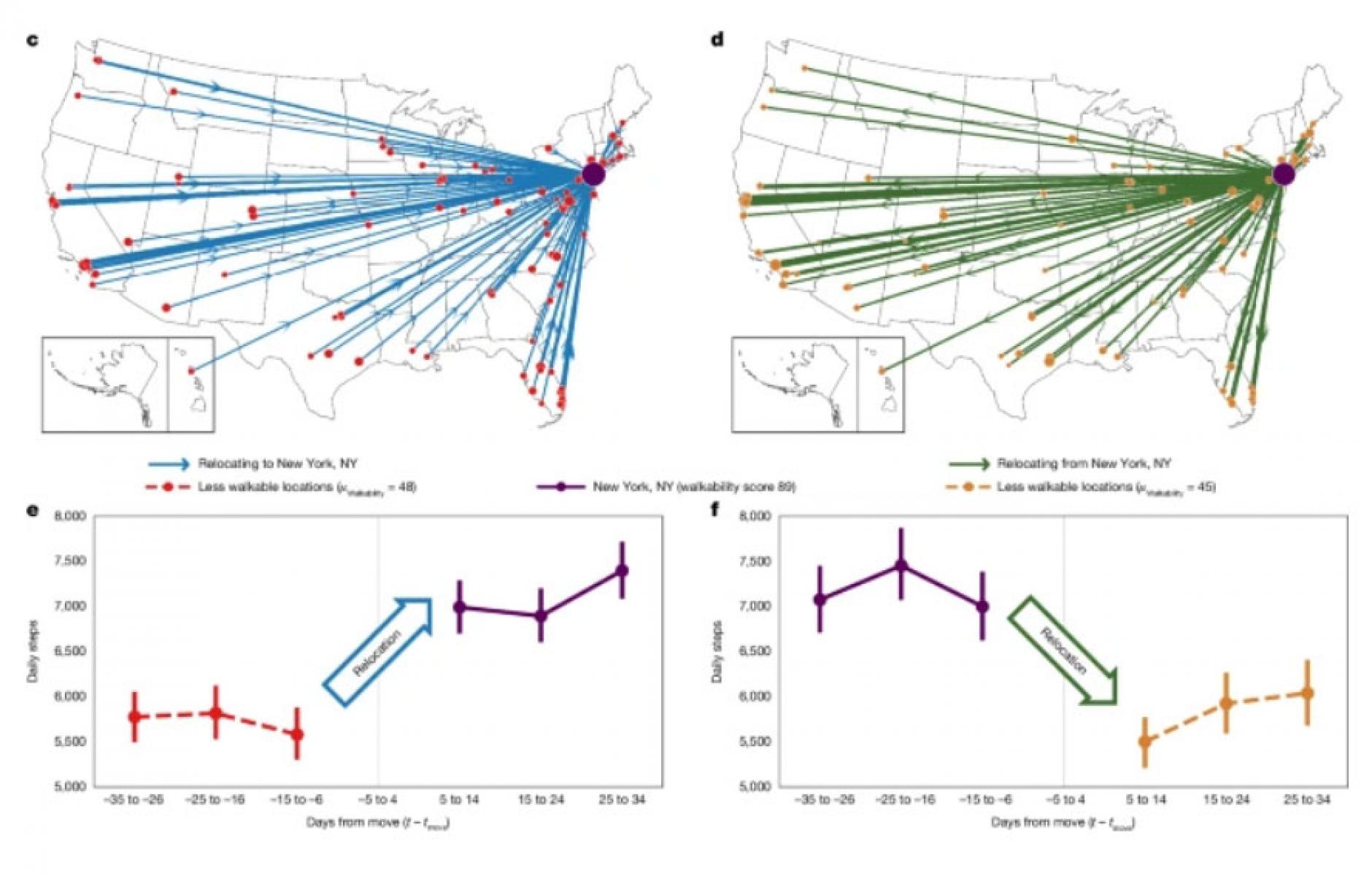

A new study published in the journal Nature addresses this debate. The authors used data from 2.1 million cell phone users nationwide to show that when diverse people move from a less walkable to a more walkable community, they walk more. When they make the reverse move, they walk less by the same amount. The effect is observed across ages, genders, and body mass indexes, and persists for at least three months, as long as the study was able to measure.

The study gathered data for 248,000 days of objectively measured physical activity, across 7,447 relocations among 1,609 cities. Moving from a less walkable (25th percentile) city to a more walkable city (75th percentile) increased average walking by 1,100 daily steps, according to the authors from Stanford University, University of Washington, and NVIDIA research.

The evidence undercuts the “self-selection bias” theory, the authors say. “If participants that moved relocated to higher-walkability locations specifically for this quality, a form of residential self-selection, we should have observed higher physical increases relative to physical activity decreases when relocating to a lower-physical-activity location. Instead, we observed point symmetric changes.” Moreover, if self-motivation is the cause of walking, this would drop off over time for many people, like going to the gym. Over the three-month time frame, that didn’t happen.

The article is called “Countrywide natural experiment links built environment to physical activity.” It’s a natural experiment, as 90 percent of people now have cell phones, enabling the accurate tracking of walking that was, for a long time, only available through surveys. My own experience leads me to believe that people may not know how much their walking changes in difference types of built environment—but their phone does.

My one caveat with this study is that they correlated actual walking with the walkability of the place through Walk Score—but this was only calculated at the city level. Walk Scores vary massively in cities. For example, Charlotte, North Carolina, has a very low Walk Score, 26 out of 100, whereas New York City has a very high Walk Score of 88. And yet moving from, say, a residential neighborhood in Staten Island to downtown Charlotte would likely mean a rise in walkability—but the study’s data would have shown it as 62-point decrease.

The overall conclusions of the study appear valid; however, more granular data on the built environment would allow for a more robust analysis and better insights into behavior.

The authors believe that changes to the built environment could yield widespread positive health effects, impacting many more people than simply encouraging individual behavioral changes. “These findings suggest that compared with interventions targeting individuals and reaching small numbers of people, changes to the built environment can influence large populations.”

The built environment is an under-explored resource for promoting health, especially if people from all walks of life are naturally more active in walkable places. “These results suggest that physical activity levels are directly influenced by the built environment and not simply a product of personal preferences or other types of selection effects,” they note.