Turning a dead mall into a downtown is not easy, but worth the effort

We are amid a massive repurposing of shopping malls in the US. Bill Fulton, author of The Future of Where substack, cites estimates of the US shrinking from 3,000 regional malls down to 200.

Alan Ehrenhalt, contributing editor of Governing magazine, explains that the malls have been dying for two decades (CNU published a short book, Greyfields into Goldfields, about dead mall conversions way back in 2002). “The peak year for malls in this country was 1982. Through the 1990s, about 140 new ones came on line each year. But few if any conventional enclosed malls have been built in the United States since 2007,” Ehrenhalt writes.

Failing malls are often located on infill sites that are served by bus transit, and they have the necessary infrastructure to support high-intensity development. Malls are being converted into schools (secondary and higher education), government offices, healthcare facilities, call centers, data hubs, megachurches, apartments, and other uses. Fulton laments that, with a few exceptions, most are not being converted to what he calls “real places.” Even after conversion to other uses, they mostly remain facilities that you drive to, do what you need to do, and then leave.

Malls originally were intended to be social hubs, places of community. That was the idea of architect Victor Gruen, who is credited with inventing the concept. Although many teenagers famously ran amok in malls in the last two decades of the 20th Century, malls were never very good at bringing people together in communities. They were always places of commerce—not multipurpose town centers. In the scramble to salvage some value in failing malls across America, creating social hubs seems to be a low priority.

What would it take to turn dead malls into real places? I was recently in Denver, Colorado, and saw two examples of cities pursuing that goal. Both are massive former mall sites—just over 100 acres each, in Lakewood and Westminster, west and northwest of the city. In both cases, planners divided superblocks containing the former mall and outbuildings into more than twenty urban blocks.

In other words, they created a street grid, which is essential for any walkability or urbanism to be built. Why build a grid? Answer: Have you ever seen a great city or town without one? Grids don’t necessarily have to be perfectly rectilinear. Streets can bend and deflect as long as they are well connected with reasonably small blocks. Street grids are the skeletons of cities, and they also correlate with surprising benefits. For example, they save lives and reduce injury accidents substantially, as traffic engineering researchers Wesley Marshall and Norman Garrick discovered in a study of 24 cities (half with street grids, half without).

The Lakewood and Westminster retrofits are impressive, yet they have also struggled. It’s not easy to take a large former single-use mall and build a vibrant downtown in its place. The first project was Lakewood, where the Villa Italia Mall died about 25 years ago. The mall, reputed to be the largest between Chicago and Los Angeles when it was built in 1966, left a physical and fiscal hole in the city.

A Denver firm with a vision, Continuum Partners, partnered with the city to create Belmar, a downtown that opened in 2004 and continued construction for another 15 years. I was astonished at the abundance of shopping and destinations available at Belmar, which spans 22 city blocks.

From the point of view of a resident or visitor, almost anything you need is within walking distance. There's a large Target, which includes groceries, as well as a Whole Foods, Best Buy, Dick's Sporting Goods, DSW, Hobby Lobby, Party City, Nordstrom Rack, Burlington, and a variety of smaller shops, including a mix of local stores and national chains. For entertainment, there are 17 restaurants and bars, a 16-screen Century Theaters, and a bowling alley. The central plaza features outdoor music, festivals, and fairs—it converts to ice skating in the winter.

There’s more to Belmar, including an abundance of medical offices and facilities, fitness studios, a few hundred thousand square feet of office space that is home to many companies, and a sizable neighborhood park. As of 2014, "more than 2,000 residents live within the 22-block area, and another 4,000 are within walking distance,” according to the Denver Post. There’s a high-end Hyatt Hotel. Walking in Belmar is safe, comfortable, and interesting, with plenty of destinations. I could be happy living there. Considering this was a giant mall surrounded by parking 25 years ago, the accomplishment is impressive.

As I indicated, the sailing has not been smooth in recent years. A company called Starwood Capital purchased the commercial portion of Belmar in 2015, which was subsequently foreclosed upon in 2021. It was reported that “Belmar has been in decline for some time,” and the pandemic exacerbated its financial woes. Starwood then sold to its current owner, Bridge33. Despite the problems, all of the major tenants that occupied Belmar 10 years ago are still in operation today. Except for a few small, vacant storefronts, Belmar appears to have recovered from its difficulties. The sheer variety within a five-minute walk would be the envy of many major downtowns. The residential aspect of the development has been successful.

City as master developer

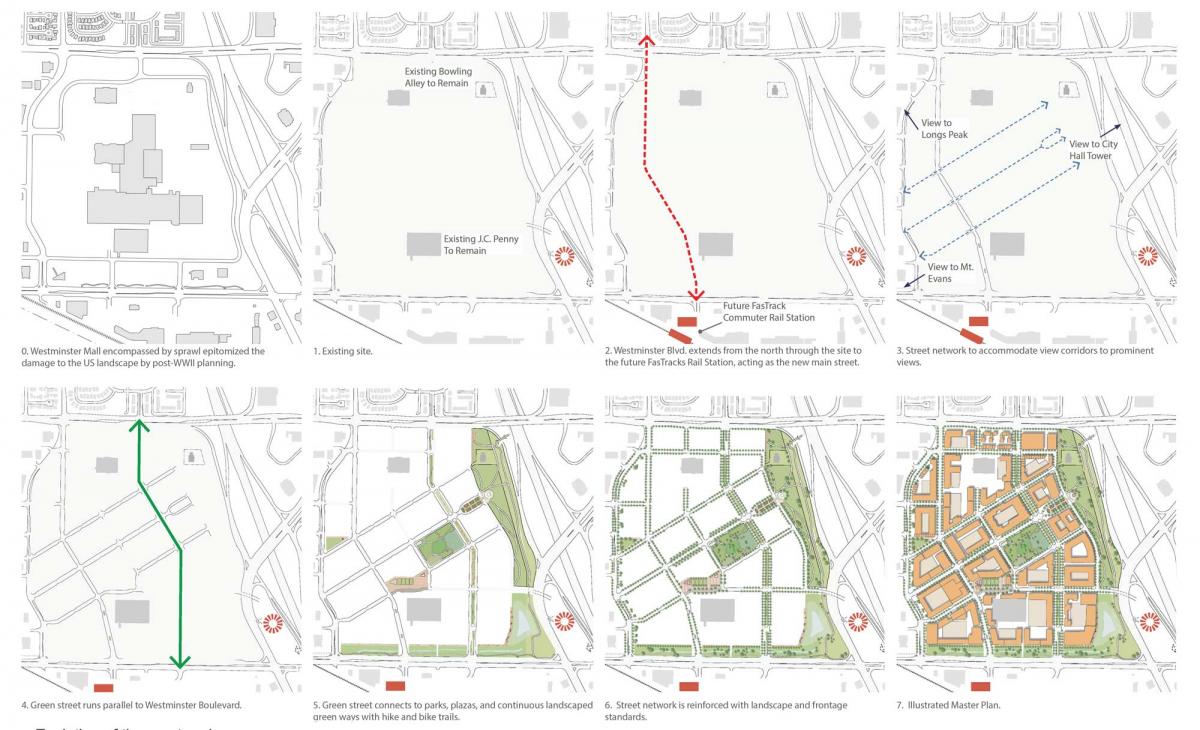

About 10 miles to the north, Downtown Westminster follows a different model. The city purchased 95 percent of the former mall's land and hired Torti Gallas + Partners, a new urbanist planning firm, to create a plan for the site.

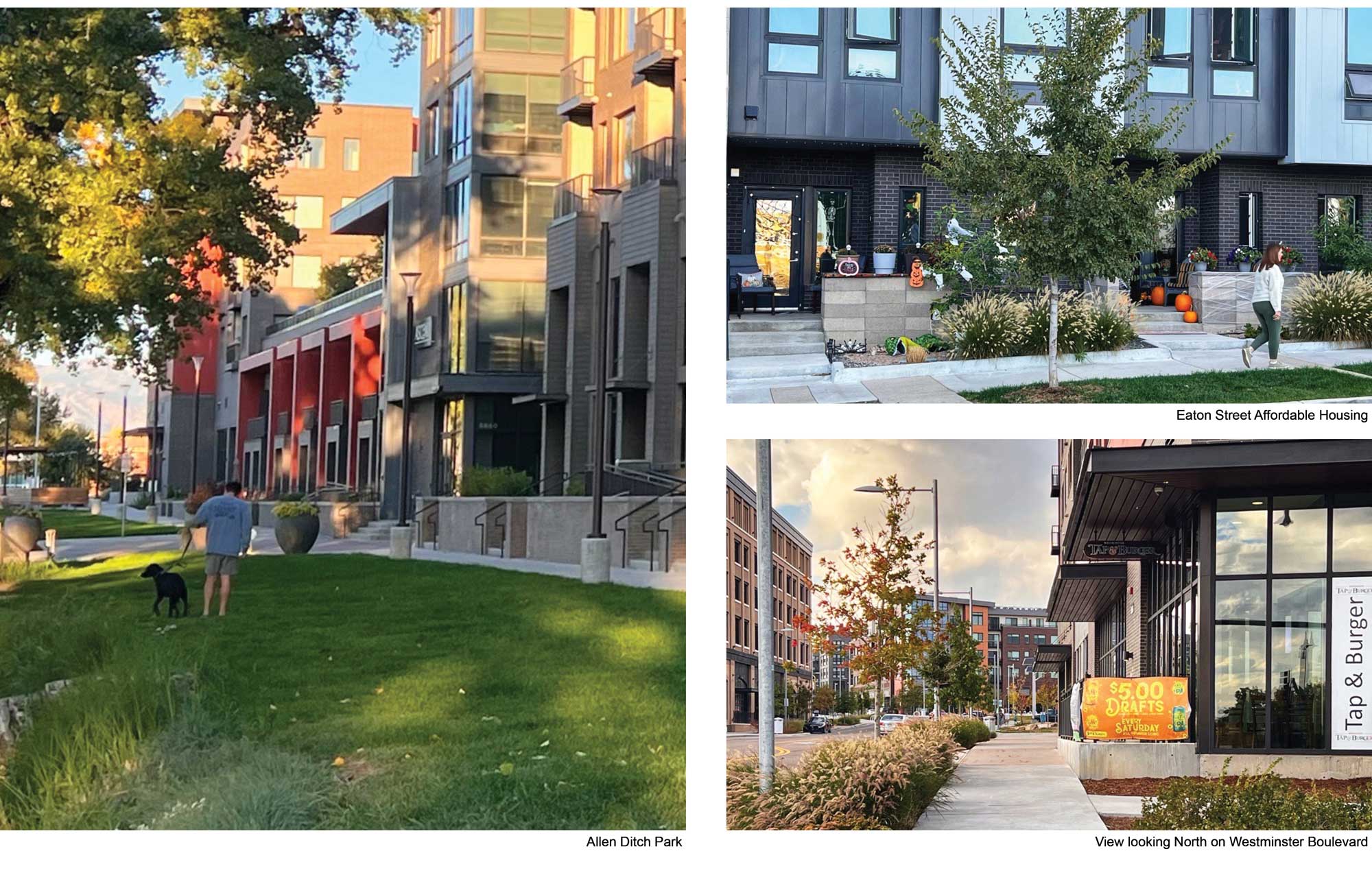

Downtown Westminster is only about 20 percent built, so it has much less to offer than Belmar. When I visited on a weekday, it was cold, raining hard, and windy. The new streets are lined up to offer views of the Rocky Mountain peaks (an example of street deflection), but on that day, there was no visibility. And yet, Downtown Westminster had some life to it. With a companion, I went to a bowling alley. Then we visited several eateries and selected one to have dinner. I enjoyed my walk in the rain.

Downtown Westminster is developing one site at a time, with the city acting as master developer. The residential portion has been successful, with more than 700 living spaces completed, including 200 affordable and workforce units. The city has recently approved the first affordable senior housing development in the area.

The mixed-use portion has struggled. A bookstore closed in 2023, and a planned food hall and office building have not materialized. There's a Wyndham Hotel, several restaurants and a bar or two, a popular coffee shop, and the Alamo Theater. JC Penney and a bowling alley survive from the old mall development. According to local writer Bill Christopher, Downtown Westminster lacks a main ‘draw’ to attract apartment dwellers or regional residents, “except for the big events hosted there, like Top Taco and Brew Fest. The area has needed an infusion of energy, vibe, entertainment, and excitement for some time.”

Recently, the City Council approved an “activation” contract with the Chamber of Commerce to provide live music, open-air yoga, and other events regularly to Downtown Westminster. Every new activity, business, service, or resident will contribute to life in Downtown Westminster. Because the City is master developer, the project moves slowly. The vision is to build the social and economic center of the City.

Why did Lakewood and Westminster choose to build a downtown on top of a street grid? It’s a more ambitious goal than simply finding a different kind of tenant. Both cities lacked significant historic downtowns. They are sizable municipalities, with more than 100,000 people, needing a downtown to match. These mall sites, with their central locations and large acreage, represented perhaps the only opportunity for these cities to establish a genuine downtown area. Each jumped into that opportunity with both feet.

Despite the difficulties, Belmar and Lakewood are taking the right path for the future. They put their faith in urbanism, a city-building approach that has stood the test of time. More municipalities with dead malls should take note: Urbanism is the reason cities exist in the first place.