Reviving neighborhood stores

Looking at a walkable urban neighborhood today, it may be hard to imagine how much mixed-use once existed. Chances are, it is far more than you think. In some cases, a former commercial building or site is obvious. In others, it is far from obvious. Often, the mixed-use or commercial building has been torn down and replaced with a residential use. Or a current residential use may look like it has always been that way.

Seventy-five or a hundred years ago, most urban neighborhoods were chock-full of businesses, including markets, eateries, bakeries, pubs, dry goods, barber shops, small industrial operations, doctor’s offices, and even small hospitals.

The topic is vitally important today, as physical retail stores are threatened by online shopping and cities struggle with vacant storefronts. Businesses are important gathering places and destinations in neighborhoods. When they disappear, a part of the neighborhood dies.

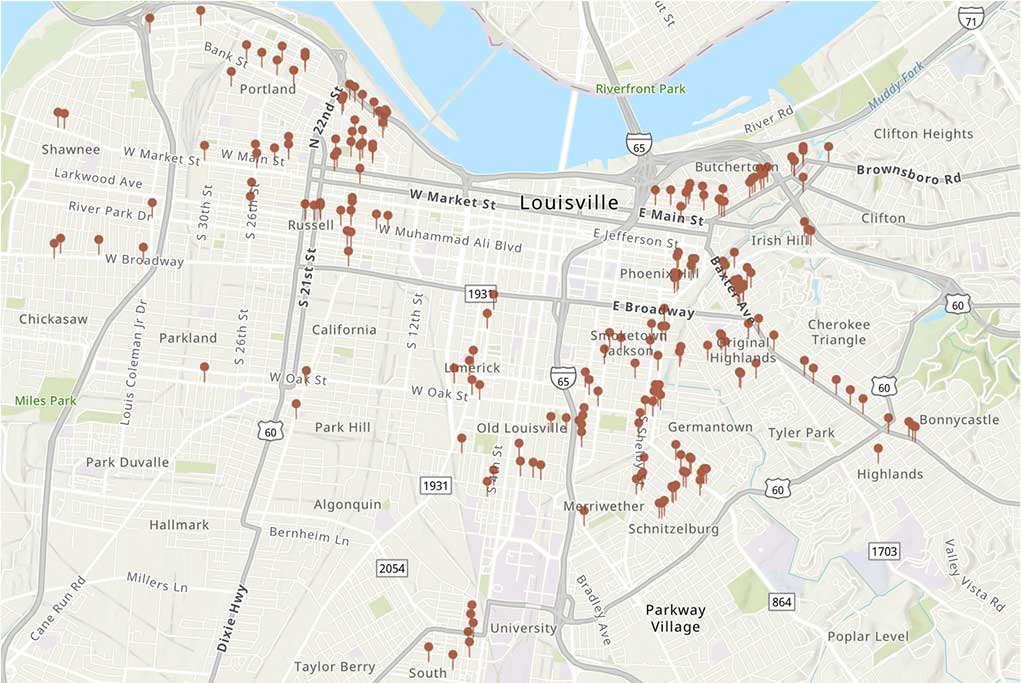

Small markets are especially important because they supply household daily needs—such as milk, toilet paper, basic prepared and unprepared foods, and over-the-counter drugs. To revive such businesses, University of Louisville is mapping out historic neighborhood store sites, so-called “ghost stores.” The city has a surprising number.

When zoning was enacted, corner stores often became “nonconforming uses,” allowed to operate as long as the same use was continually maintained. When a store goes out of business, however, the grandfathered commercial use goes away. If somebody were to try to start a business today, years or decades after the previous business went away, they would face an uphill battle. As more corner stores go out of business in otherwise residential areas, the commercial use right may also go away.

Off-street parking requirements are another corner store killer. To meet parking requirements, the store would have to build a parking lot—often knocking down an adjacent building. That would make the business untenable or damage the urban fabric.

Another problem is the business model, which is changing. Prior to supermarkets, everyone shopped at neighborhood stores. That made them profitable businesses. Now corner stores face stiff competition from large grocery stores and online shopping, delivered to the door. These days, small markets take the form of “convenience stores” attached to a gas station. The food offerings are junk—with 100 varieties of sugary drinks and chips—but nothing to prepare a meal.

But neighborhood markets still serve a vital social function, especially for those who don’t drive. They give the young and old additional independence. Children may learn to shop and use money at the corner store. If residents have destinations to walk to, they will get more daily exercise and likely have more social contact.

The Seven Market and Cafe in Seattle, shown at top, could be a business model. It’s a cafe and corner store in one, which doubles the business potential. It’s a “third place” for the neighborhood, a place to meet casual acquaintances, plus real food.

Mapping historical corner store locations is a start. Such a project could identify zoning issues that need to be resolved before a business can be launched. Once the zoning issues are resolved, more needs to be done. Maybe some incubation of neighborhood markets is needed. A mentoring program and community college course, perhaps. Maybe the cooperative extension should have a program, especially if corner markets sell local produce.