Increasing access to opportunity

Jarrett Walker’s book, Human Transit: How Clearer Thinking About Public Transit Can Enrich our Communities and Our Lives, changed how many people understand public transport. This month, Walker’s new edition of the book is substantially rewritten and addresses current trends that have taken hold since Human Transit was originally published in 2011.

Planners and real estate professionals are still making big mistakes in their thinking about transit, including undervaluing buses and their contribution to urbanism, Walker contends. Although new urbanists design and build walkable, compact development that is more efficiently served by transit, they often don’t understand the important concept of “linearity,” Walker argues in a recent CNU On the Park Bench webinar.

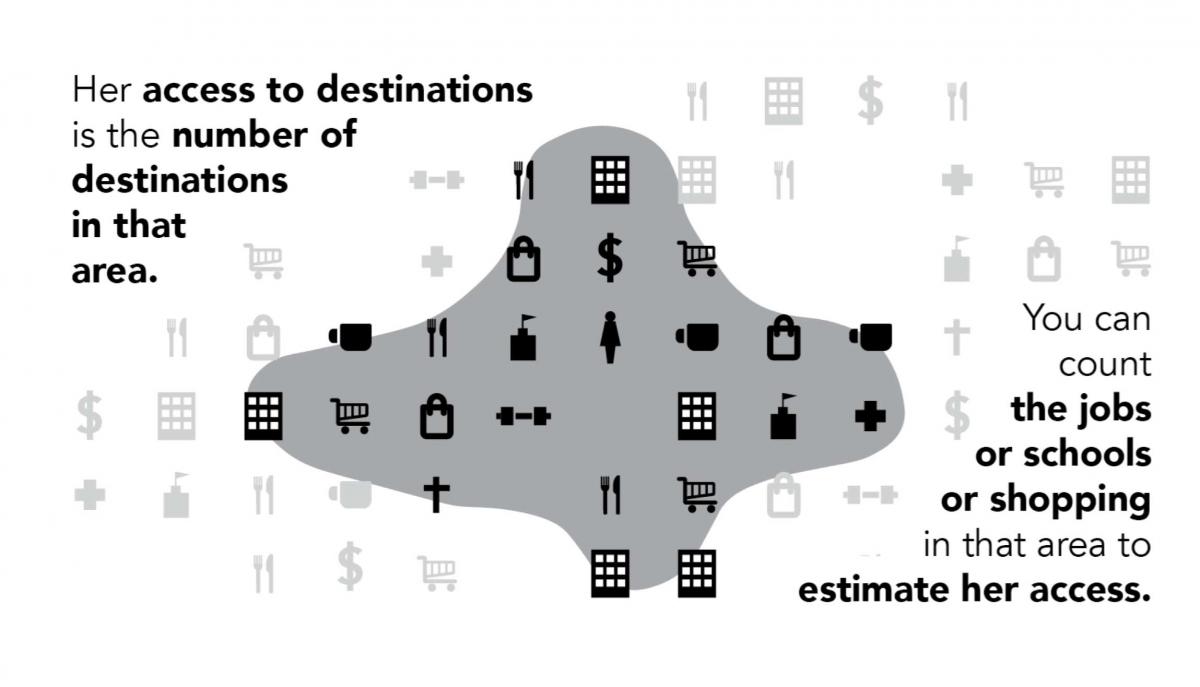

Many transit systems are being redesigned to boost “access to opportunity,” which he explains is the most important conceptual shift in transit in recent years. He depicts “access to opportunity” as an image with a person at the center, surrounded by a blob shape, depicting how far that person can get in a specific amount of time.

“There are two ways to increase access to opportunity. One is to make the blob bigger—that’s transit. The other is to put more things in the blob. And both of those things enrich this person’s life.” He describes this access as “freedom” and limits to that access as “the wall around your life.” In some ways, access to opportunity is similar to the new urbanist “15-minute city.”

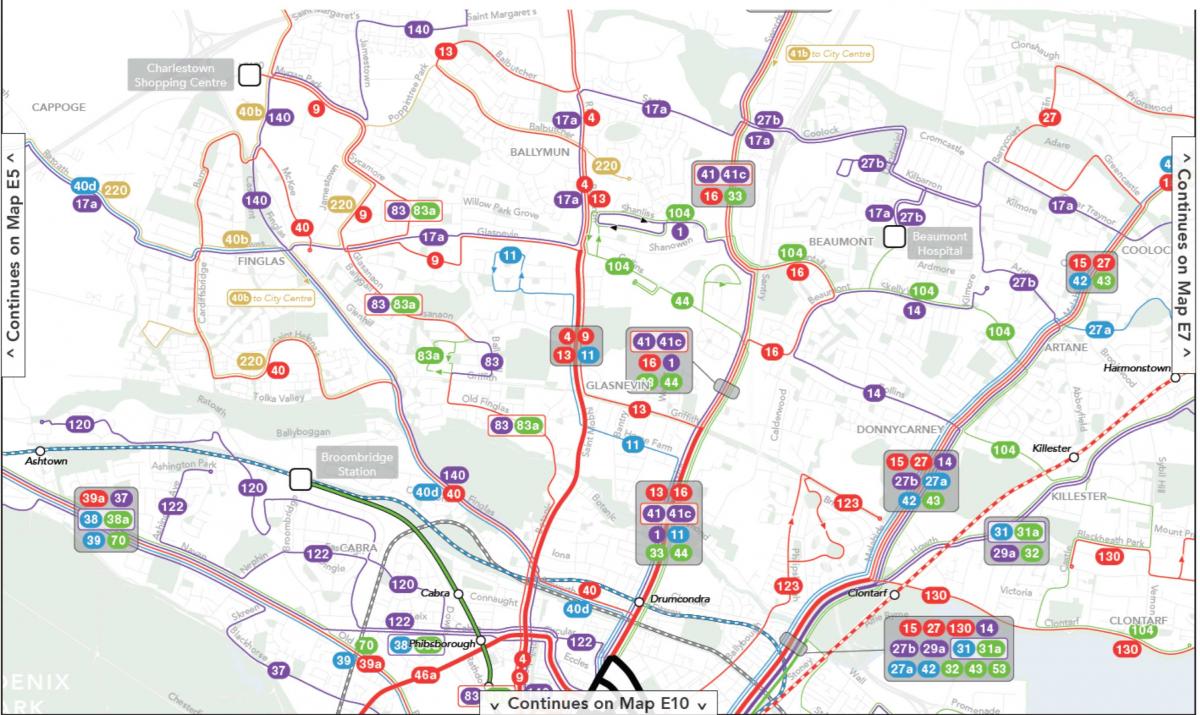

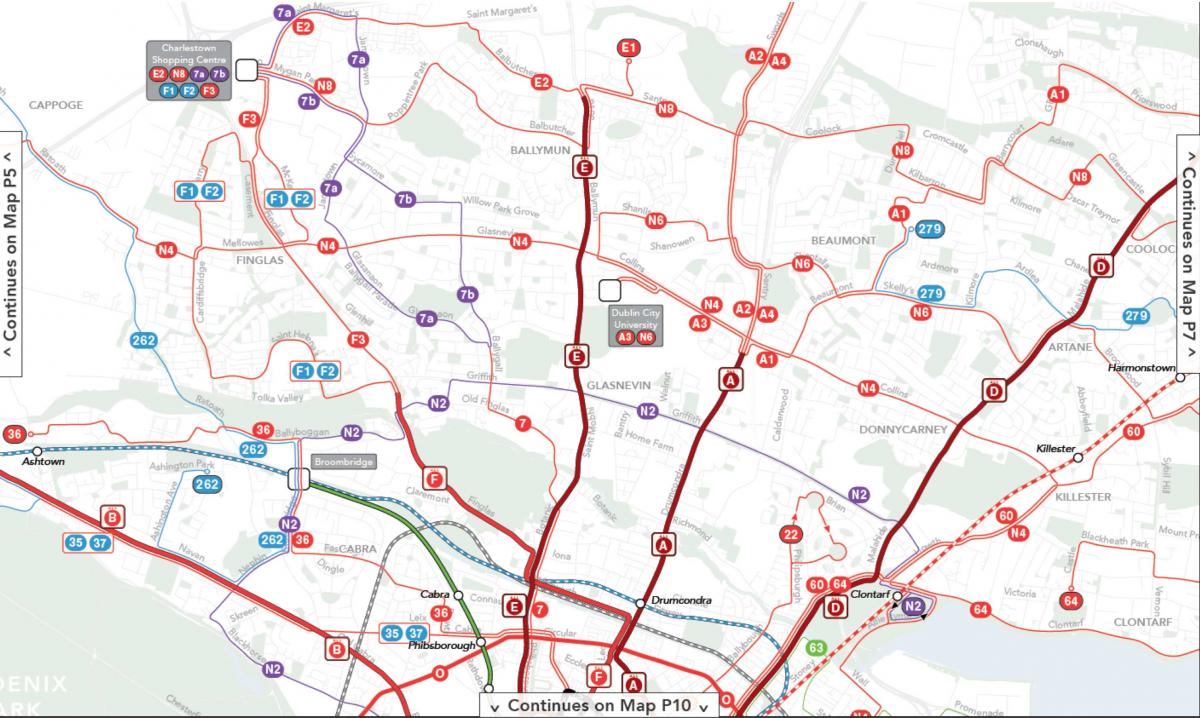

Tools have become available to analyze and redesign metro transit systems to optimize access. The image at the top of the article shows the access expansion in Dublin, Ireland, due to a recent transit system redesign. The whole point of cities is for people to be able to access many opportunities, Walker explains. When transit systems enable people to access more jobs, services, and other opportunities, they get more riders. “Access is turning out to be a remarkably good predictor of ridership,” Walker says.

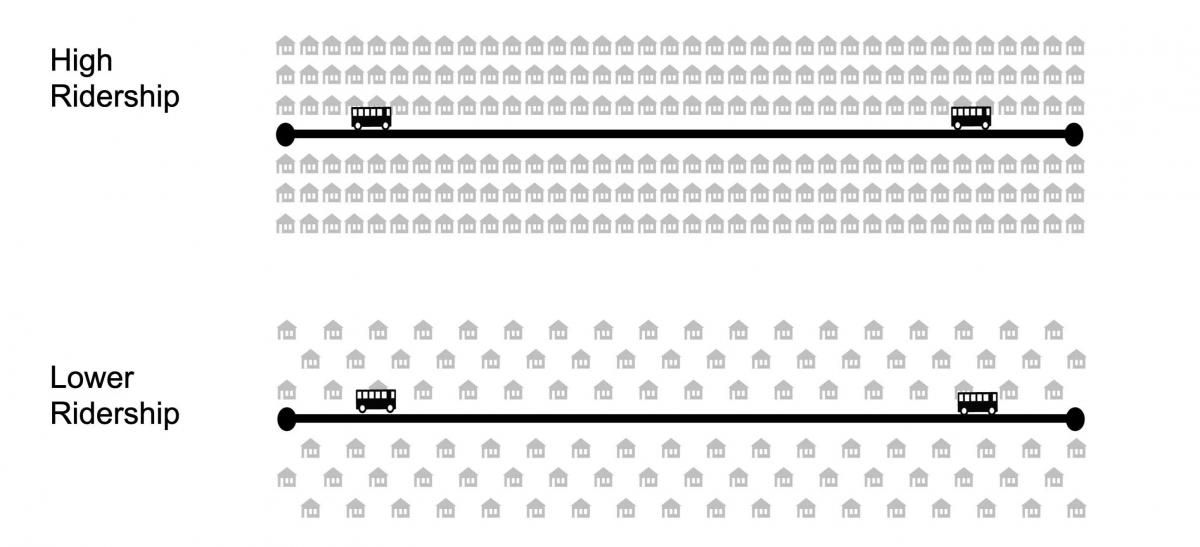

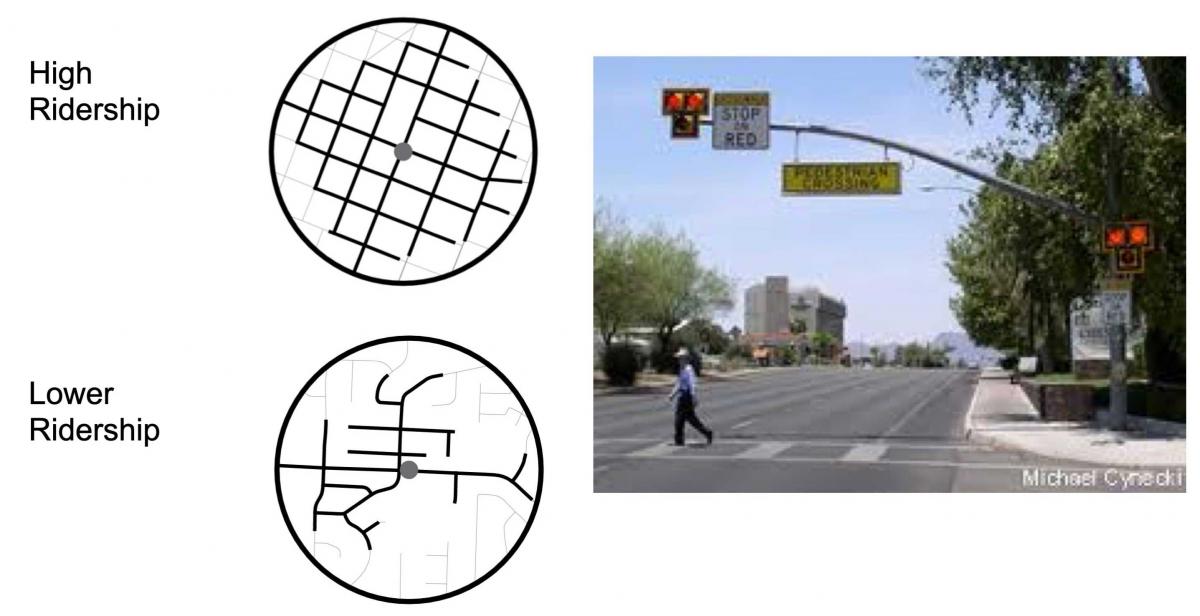

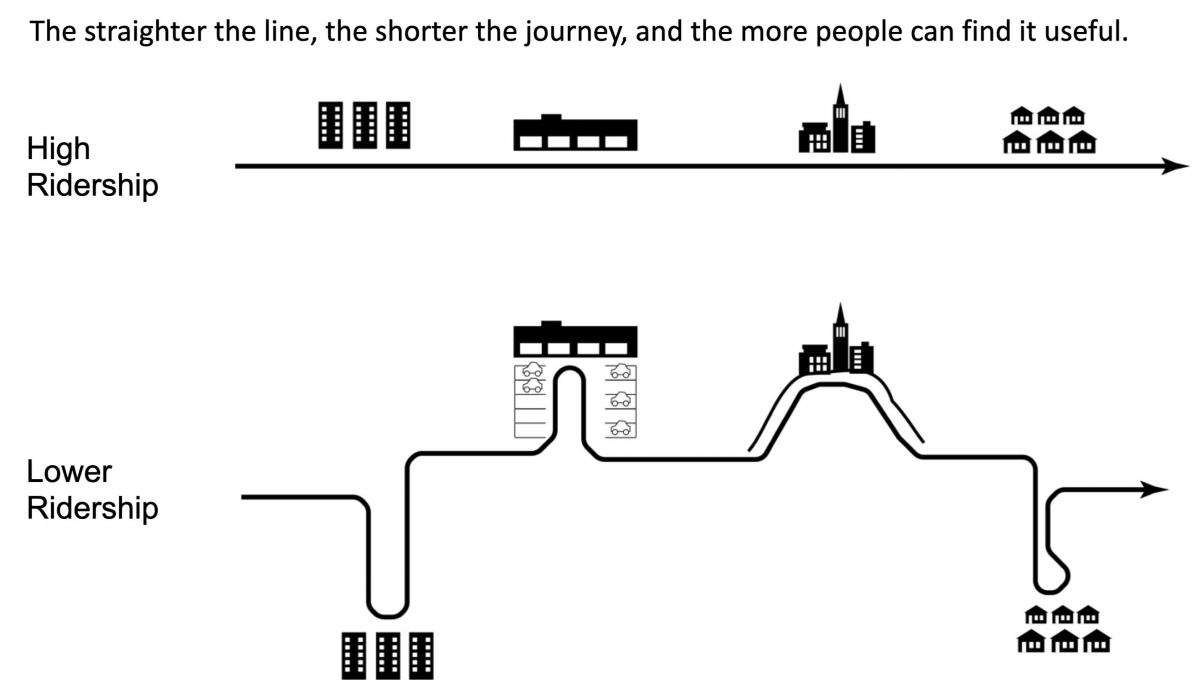

Three geometric qualities of land use that most affect transit use and effectiveness, Walker explains. They are density, walkability, and linearity. The more dense, walkable, and linear the development along transit is, the higher the ridership and the greater the access, he says.

New urbanists almost always design walkable, compact development—even in the suburbs. So the first two qualities are covered by New Urbanism. However, urban designers often don’t understand the concept of linearity in transit—including many new urbanists, Walker argues.

“If you run transit in a straight line, it’s more efficient and you can provide more frequent service. Also, people want to travel in something they perceive to be a straight line.”

The problem is that people who decide the location of government and health care services, jobs, college campuses, retail and other places people want to go often put the buildings far from the main route. These choices have created a “geography of tyranny toward low-income people—geography that forces people to own cars, or forces transit to do very expensive things.” This has also been true, sometimes, of new urbanist town centers.

“I do appeal to people working on greenfield New Urbanism to think carefully about this and where you are on the (transportation) structure, and to try to avoid creating these problems where an entire new urbanist development is effectively a cul-de-sac.”

Buses versus trains, and BOD

Walker says that many planners think of buses as inferior to trains, yet most transit users don’t think about technology. They simply want to be able to get where they need to go with reliable and frequent service. Nationwide, about half of transit trips are by bus. Heavy rail makes up 38 percent of trips, most of which are in New York City. Light rail, despite large systems being built in cities across the US, accounts for 5 percent of transit riders. And yet, transit-oriented development (TOD), is typically defined as development around a train station. Walker asks: “What if the definition of TOD is not development next to a train station, but development in areas that have good transit?”

Bus Oriented Development (BOD) is more important than many people think, Walker says. Many high-frequency bus routes support dense, walkable development—but a circular definition of TOD prevents it from being labeled as such. “Buses are simply transit on pavement, rather than rails. Since we have mostly pavement in US cities, not rails, the most cost-effective way to expand transit is to run transit on pavement.”

Meanwhile, post-COVID bus ridership is bouncing back faster than the recovery of many rail systems, Walker notes. That trend will likely continue because rail systems tend to deliver riders to employment downtown, which has declined due to remote work, he explains.

One problem with bus systems is that they have been laid out over many decades in overly complicated patterns, which he calls “spaghetti.”

In Dublin, Houston, and many other cities, his firm replaces the spaghetti with simpler, more legible, and frequent service. “When we lay out a bus network, we try to find and bring out the new, strong, high-demand corridors that we think are permanent. And that permanence lies not in whether there are rails in the street, but in the permanence of the market that is there in the land-use pattern.”

These rerouted systems are creating access, which in turn builds opportunity for mixed-use, walkable neighborhoods. “We need to educate the real estate industry about the importance of these tools in urban real estate,” he says.

New urbanist planners and developers are paying too little attention to transit network redesigns, he says. “Getting involved in those conversations when bus networks are being talked about would be a really powerful for new urbanists to do.”

See the entire webinar: