California zoning reform: Are form-based codes the answer?

California adopted legislation last week that would allow duplexes on single-family lots, effectively ending the Golden State’s era of exclusive single-family zoning. At the same time, the state streamlined the process for cities approving small multifamily buildings in infill and transit-oriented sites. Two laws signed together by Gov. Gavin Newsom, SB 9 and SB 10, are designed to create more housing in a state with the highest dwelling costs in the US (median price more than $800,000).

The laws have important urban design implications, as they advance the state’s policy move toward objective, non-discretionary development standards. Practitioners skilled in form-based codes (FBCs) will likely see demand for their services rise as cities are forced to give up the micro-managing of design by planning commissions and city councils. Cities still want design control, and new urbanist FBCs—designed to legalize compact, walkable neighborhoods—offer the clearest path to achieve that goal.

The legislation requires jurisdictions to approve projects by-right, without a discretionary design review process, says California planning consultant Lisa Wise. “So, yes, we anticipate increased demand for objective design standards and form-based codes at least in high-demand areas and jurisdictions with the resources.”

SB 9 is the most far-reaching. Not only does it allow duplexes on single-family lots, it allows lots to be subdivided into two, each of which could have a duplex. That means up to four units on what are now single-family lots. The law applies to more than six million lots across California, according to an analysis by the Terner Center at UC Berkeley. Taking into account market feasibility and other factors, the law may enable up to 700,000 new living units, the report concludes. That’s a high number in a state that currently averages the construction of fewer than 90,000 residential units a year.

“Since the vast majority of the residential land in California has single-family zoning applied to it, SB 9 affects the vast majority of the residential land in California,” notes planner Patrick Siegman of Siegman & Associates.

The law includes restrictions to prevent displacement and land speculators from taking advantage of the provision wholesale. It does not apply to units that have been occupied by tenants in the last three years, for example. SB 9 also restricts off-street parking requirements—to zero if the lot is located near transit or served by car-share. From the point of view of new urbanists, the latter provision is huge—and it may enable small-lot bungalows and other housing that has not been constructed in a long time.

SB 10, on the other hand, does not specifically allow more housing units, but it enables cities to bypass environmental review for projects of 10 or fewer units on infill sites or in areas served by frequent public transit. It restricts private lawsuits on such projects. “It allows cities to do what they want to do, or need to do, quickly and not have to spend ten years doing [environmental impact reports] and getting sued,” said State Sen. Scott Wiener, who sponsored the law.

Form-based code implications

The state has strongly promoted “objective design standards” in recent years. California’s notoriously slow and costly land-use entitlements can be attributed largely to two factors, notes Stefan Pellegrini of Opticos Design in Berkeley. The state’s stringent environmental review requirements may add a year to the entitlement process—more time if lawsuits result from that review. SB 10 addresses environmental review in small infill multifamily projects, which arguably require less environmental oversight, Wiener says.

The second factor is the culture of discretionary design review. “In many ways it has become a tradition,” Pellegrini says. “Local officials jump all over the details of projects and stretch out the hoops that developers need to be jump through for approval.” Planning commissions, and even city councils, may change the design of developments. Projects may have to go through a score of design iterations, which is time-consuming and costly. While this process has grown in response to a lot of bad development over decades, in practice it is frequently used to scale down projects and reduce density, he explains.

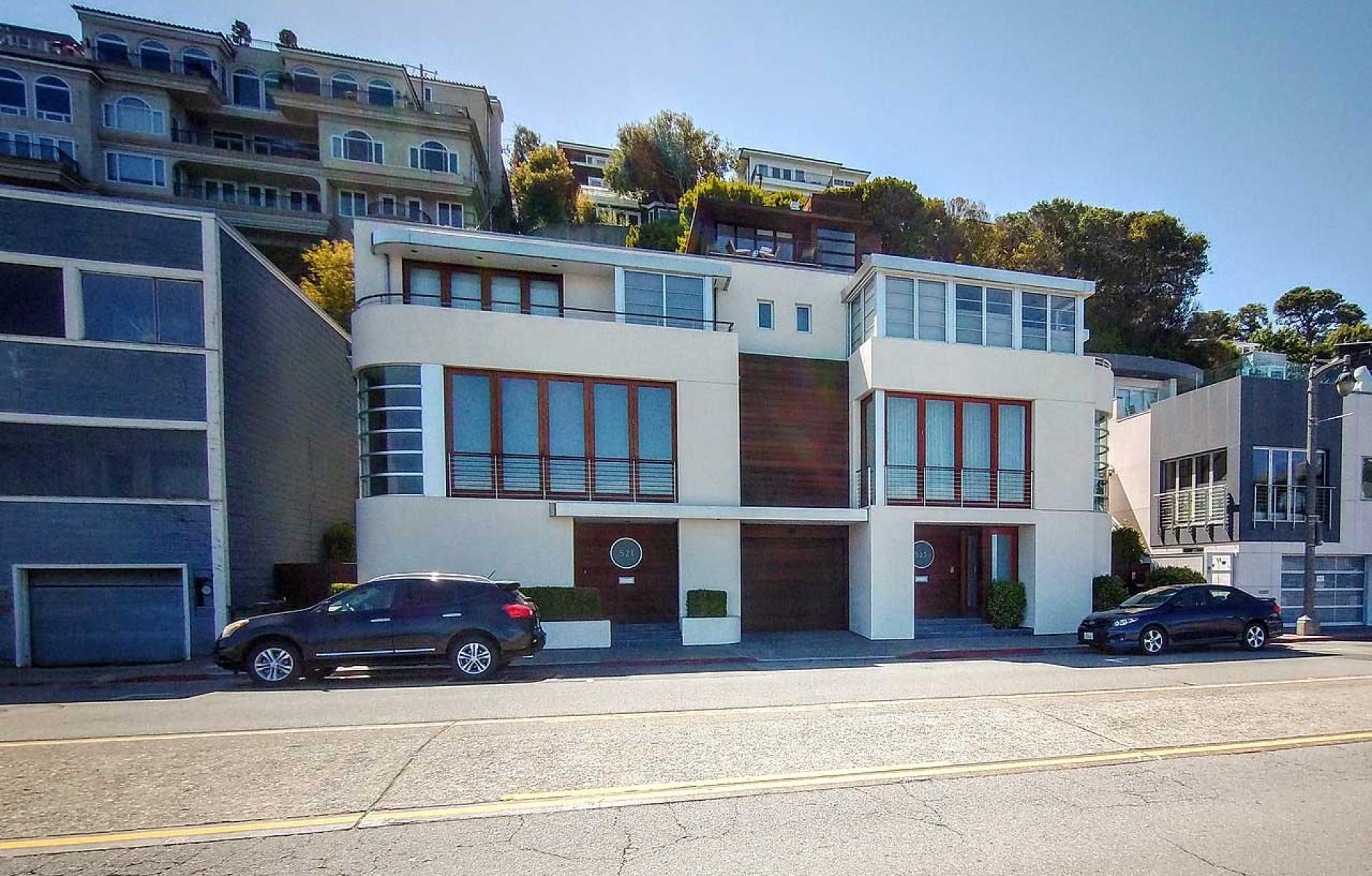

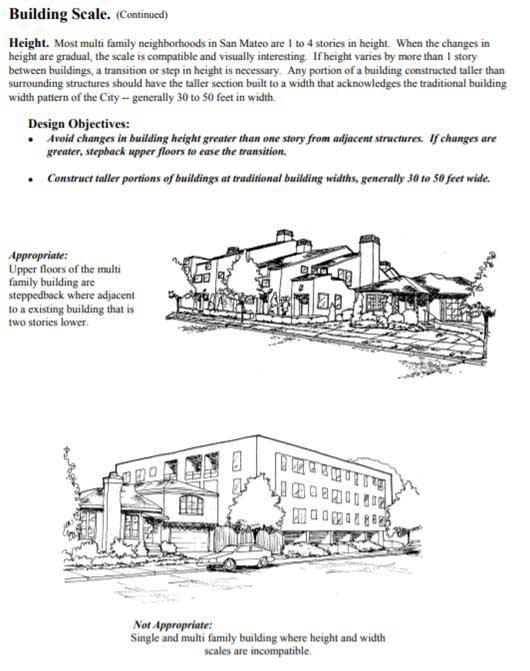

The state now includes language in land-use reform laws that calls for review based on “objective standards.” That language appeared in SB 35 in 2017, and then in the Housing Accountability Act. SB 9 specifically calls for “objective standards,” and this is defined to preclude subjective, discretionary design review. Just a few days ago, Siegman points out, a court struck down a decision by the City of San Mateo based on vague guidelines for building scale. The guidelines say, for example, that a “single and multifamily building where the height and width are incompatible” is “not appropriate.”

FBCs, on the other hand, are written with the goal of predictability. They can be applied administratively, which is what the State of California is calling for. And yet FBCs do focus on form, or design, of development. “Form-based codes are an excellent way to establish objective design standards,” says Siegman. “Graphically-rich form-based codes are also an excellent way to communicate objective design standards. New urbanist practitioners … have been criticizing wishy-washy subjective standards for decades, so it makes sense that many cities are turning to them for assistance.”

This focus on objective standards has spread geographically—first adjacent to train stations, then priority development areas, multifamily zones, and commercial areas where residential is allowed, Pellegrini says. Now, with SB 9, this applies to nearly all zones residential areas. SB 10 doesn’t specifically mention objective standards, but if cities want to apply design standards to these small multifamily projects, the Housing Accountability Act requires that they be objective, also, Siegman says.

Cities are responding in one of two ways. One option is to take current subjective standards and strike out anything that is subjective. And what does that leave cities with? The other choice is a FBC, and many municipalities are adopting that approach by hiring experienced new urbanists (state funds have been made available to reform local zoning). Marin County and ten of its cities are working with Opticos Design on a toolkit of form-based standards, for example. Wise is working with a number of municipalities, including the City of Los Altos with Opticos.

Other impacts of the law

SB 9 may be categorized as a follow-up to a 2016 law which allowed accessory dwelling units (ADUs), another missing middle housing type, on single-family lots statewide. The ADU law has dramatically increased the construction of this type since 2018, and ADUs now makes up 40 percent of housing building permits in Los Angeles, and 38 percent in San Jose, according to the Terner Center. SB 9 prohibits duplex conversions on lots that already have ADUs, unless cities choose to allow them.

One difference between these two laws is that SB 9, with the lot split legalization, allows for more affordable homeownership options on lots as small as 1,200 square feet (e.g., 20-feet by 60-feet). “SB 9 has potential to expand the supply of smaller-scaled housing, particularly in higher-resourced, single-family neighborhoods,” the Terner Center notes.

The parking provisions of the bill, which have not been widely reported, will impact urban design and the architecture of housing that is built. The bill limits parking requirements to one space per unit, which is significant in itself, but also eliminates parking requirements entirely if the lot is within a half mile of a major transit corridor or station, or within a block of car-share. “It means that some of the wonderful housing styles of the 1920s, built before minimum parking mandates were adopted, can now be revived,” Siegman says.

SB 9 and SB 10 are adopted in the context of a national code reform movement in states and cities where missing middle housing types are being enabled in zones that used to be single-family-only. “I think this adds a lot of fuel to eliminating single-family zoning,” Wise says. “A lot of people now understand the negative impacts of exclusionary zoning. That said, we're also worried about a backlash (at least in California) to the state taking away local control.”

Where municipalities do not adopt objective standards that address form, owners and developers have the potential to shoe-horn in some ugly development, she explains. The Terner Center analysis shows that change is likely to be incremental, which would give municipalities an ongoing opportunity to respond with better objective design standards.