The corridor model for more affordable housing

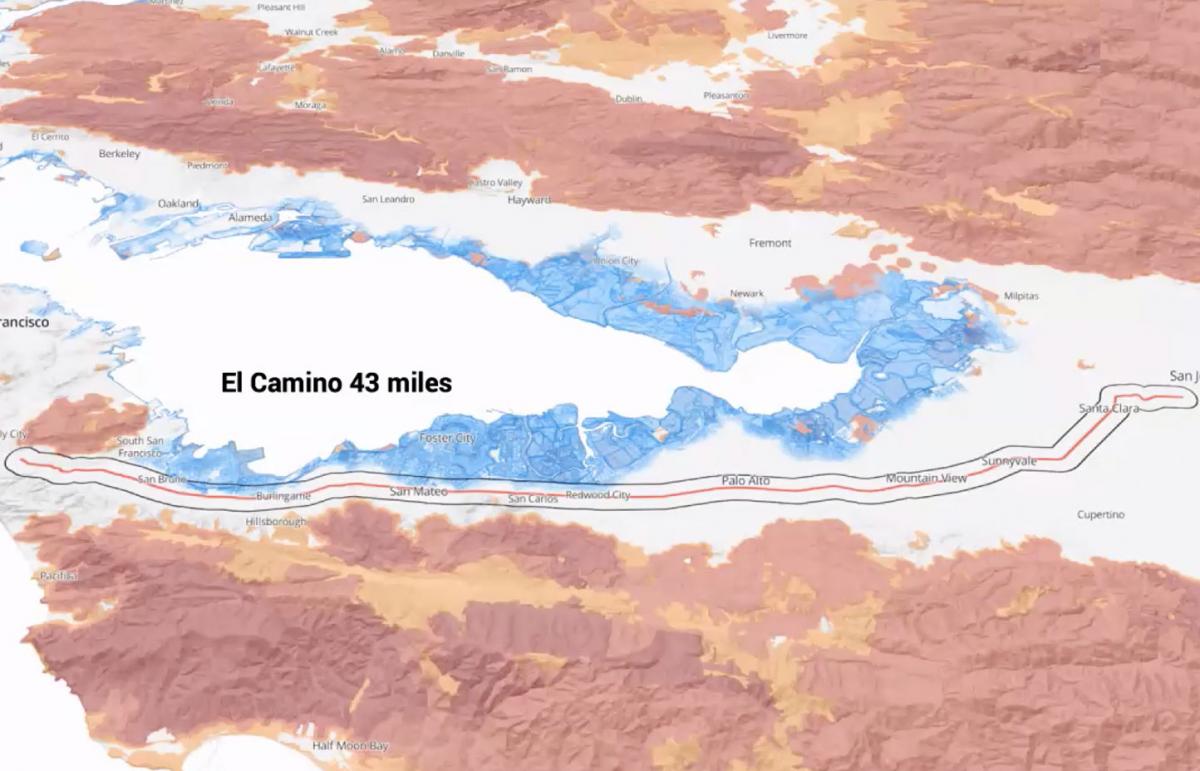

El Camino Real may be the greatest suburban commercial corridor in America, stretching 43 miles from Daly City to San Jose—in Silicon Valley, California. It also shows the promise of suburban arterial roads in solving America’s housing problems.

Like many suburban arterials, El Camino Real inefficiently utilizes its wide right-of-way (ROW), and the land adjacent to the ROW—which is dominated by surface parking lots and low-rise single-use buildings.

An analysis by Peter Calthorpe of individual parcels on El Camino Real shows that the thoroughfare could handle an additional 250,000 multifamily homes, 20 percent of which could be designated as affordable housing. Better use of the 120-foot ROW would convert the current six-lane thoroughfare to one that includes bus rapid transit (BRT), generous sidewalks, and bicycle lanes—while retaining six lanes of through traffic. “We squander land in our right of ways, just like we squander land that sits on the edge of the right of ways,” Calthorpe says. The case study was presented at CNU 28.

Just this thoroughfare could go a long way towards making up for Silicon Valley’s shortage of 600,000 housing units—one that raises household costs and forces workers to commute long distances from distant suburbs, all while generating massive carbon emissions.

El Camino Real sits on the perfect terrain for development, away from both the flood and fire zones, Calthorpe told CNU attendees. The deep parcels along the highway are good for multifamily development with ground-floor commercial uses.

“We are able not only to build a quarter million houses on one strip, but we can do more affordable housing,” he says.

Households on a redesigned El Camino Real would save $3,100 in transportation costs and 45 percent in household carbon emissions, drive 33 percent less, and use 13 percent less energy compared to typical Alameda County household, Calthorpe says.

Analysis of all arterial roads

Calthorpe’s team analyzed the five county Inner Bay Area and found that 1.2 million housing units could be built on all of the strips. “This spreads the problem-solving out in the Bay Area,” he says. “It lets every community to take its share,” he says. “The development is clustered near transit, converts underutilized lands, increases the tax base, and there is no residential loss (no teardowns of existing residential).”

Depending on the size of the arterial and the depth of adjacent lots, the case study looked at different heights of residential and mixed-use buildings, from six stories mixed-use to townhouses. “With that full range, we are able to develop a capacity of 1.2 million housing units,” he explained.

While at least 20 percent of the housing could be affordable, much of it would be market rate. “We are not going to solve affordable housing needs just by subsidies,” Calthorpe says. “Subsidies are essential, but we need to rebalance supply and demand to the point where the normative house is not out of reach, and that makes the affordable house easier to achieve.”

He explains: “Affordability is a domino effect. The less entry level housing we have, the more pressure there is on rental housing. The prices go up, and affordability goes down.”

Bus rapid transit

When a corridor is more efficiently utilized in terms of housing, transit is needed, he says.

“BRT we know is the most affordable kind of transit,” Calthorpe says. “The good news about using arterials and the strip is that that’s what’s at your doorstep—the possibility for BRT.

“I think there is something better in the future than straight BRT, which is slow. It is the most affordable and equitable that we can get to right now. But there are autonomous buses coming from China, which will reduce operating expense. Anything that reduces the cost of transit enhances its reach. The more affordable transit is, the more you can build, and the more effective it becomes.”

One advantage to building in the suburbs is that land is more affordable than in cities like San Francisco. The potential for greater values on El Camino Real means that those values could be captured to pay for needed improvements, he says. “The public sector is not benefitting from the full utilization of what the property tax could be,” he says. Adopting a TIF (tax-increment financing) would mean increased property tax could pay for transit, enhanced parks and schools, and to subsidize 20 percent inclusionary zoning. “You do those numbers and we are talking billions of dollars in TIF to enhance communities in a way” that would make residents more receptive to massive infill. “There’s all kind of virtuous cycles in this particular strategy.”