A suburban town looks at retrofit options

Amherst, a 122,000-population suburban town adjacent to the City of Buffalo, New York, is going through a transition. Buffalo's mass transit line is planned to be extended into Amherst, presenting an opportunity for mixed-use, transit-oriented nodes.

This suburban retrofit opportunity would position Amherst to serve a changing real estate market—especially related to young adults associated with the University of Buffalo, a major economic engine for the town.

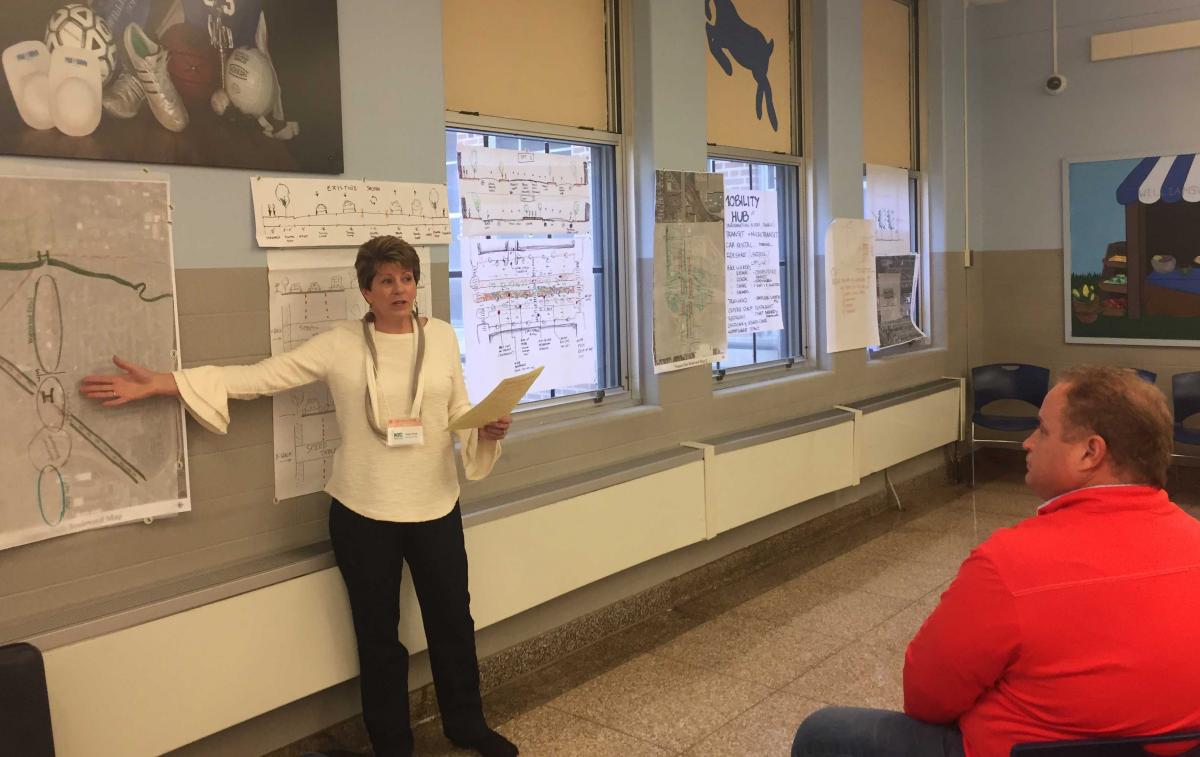

A remarkable day-and-a-half event took place in mid-October to help the Town crystalize its vision—sponsored by the Town and CNU New York chapter. The first day was entirely taken up by tours, presentations, and discussions. The following half-day was devoted to drawing of ideas.

The participants were divided into five teams who worked feverishly for a few hours and then presented. Nonprofessionals rolled up their sleeves along with the professionals. The Town's highest elected official, Supervisor Brian Kulpa, is an architect who led one of the teams.

The results were impressive—especially for the short time period involved. The ideas were roughly drawn and not all will prove economically feasible or politically successful—but they all have value as visions that can be explored. Suburban retrofit, the idea that underperforming assets in suburbs can be transformed and reused, surely has legs in a place like Amherst. Retrofit ideas included the redesign of a major car-oriented commercial strip thoroughfare, the redesign of a struggling mall, a mixed-use town center near a college campus, a new transit route, and more.

One team looked at the Boulevard Mall on Niagara Falls Boulevard, which opened in 1962—an underperforming asset in 2018. Two of its primary anchors, Sears and Macy's Men & Home, closed in 2017. Late last year the owner turned the mall over to its lender to avoid foreclosure. The transit line could go through the mall site. The team re-imagined the site, focusing on mixed-use and a walkable urban center.

Two sub-teams drew alternatives (see drawings above), and both plans had much in common. They included:

- The reuse of some commercial spaces with daycare/preschool facilities, community rooms, "third places" such as coffee shops, medical/wellness services, and other new uses.

- A connected street network with walkable blocks and pedestrian/bicycle-only streets in some locations. Current surface parking could be replaced by on-street parking and parking embedded into blocks.

- A central park for community gathering, performances, a playground, shade, stormwater retention, and popup/kiosk businesses.

- Routing the proposed transit off of Niagara Falls Boulevard to an adjacent parallel street with housing, trees, mixed-use, and stormwater/green infrastructure.

- Lots of housing, especially the "missing middle," or mid-density, types.

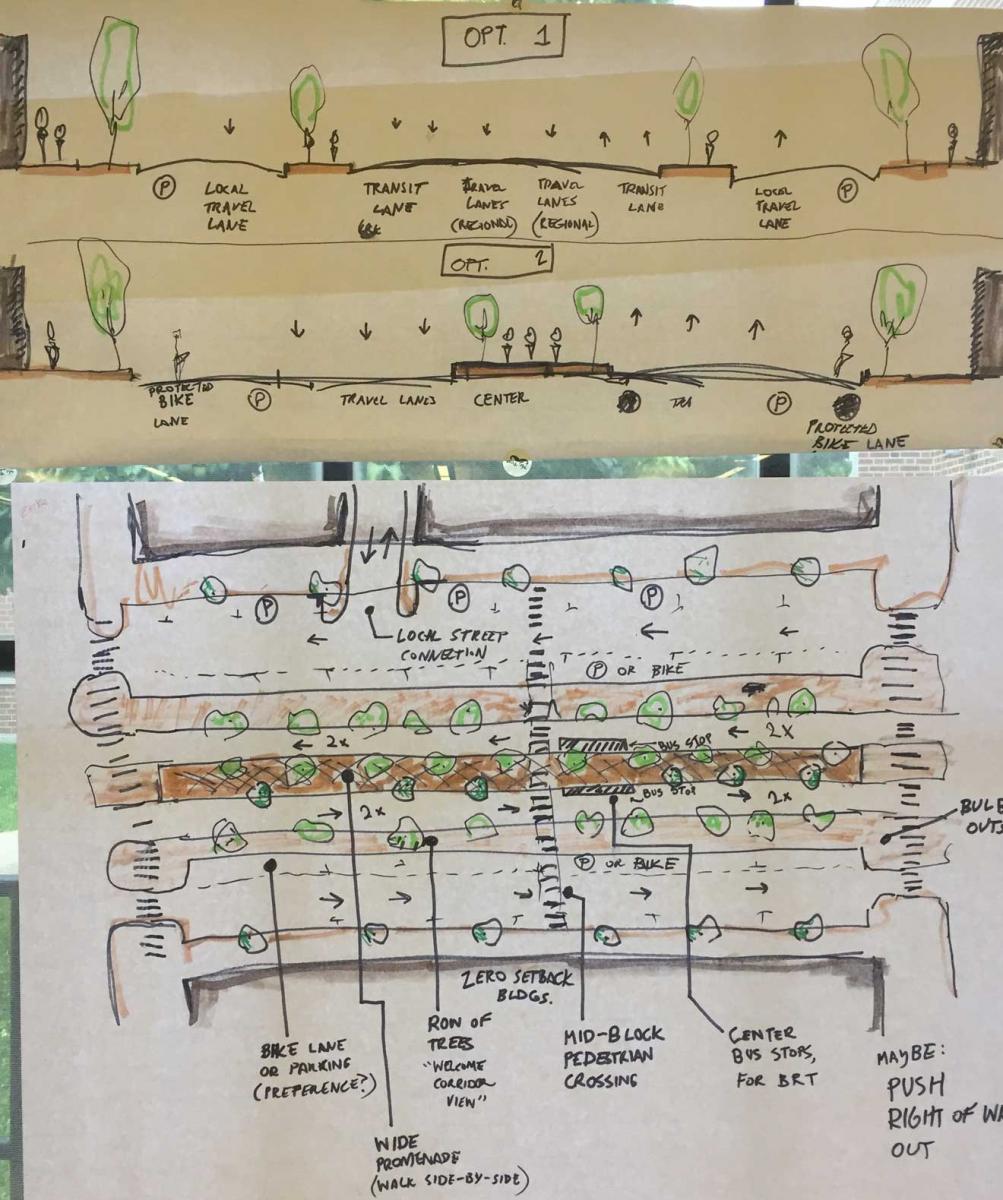

I was on a team that looked at Niagara Falls Boulevard itself, an extra-large arterial thoroughfare that is lined with car-oriented commercial development. Prior to the Interstate, this was the main route to Niagara Falls. The team explored how to calm this thoroughfare and make it work on a human scale.

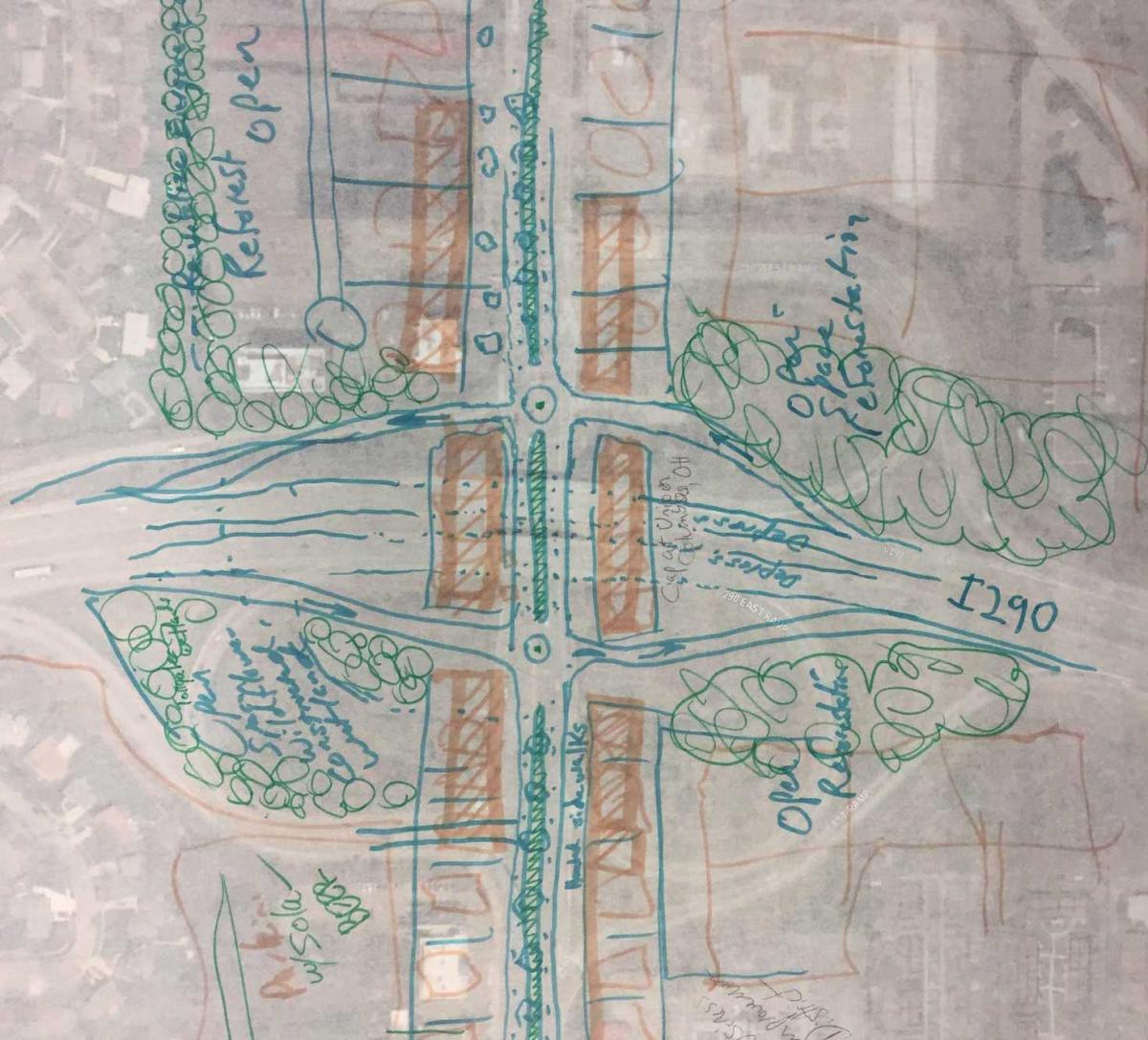

Niagara Falls Boulevard has a range of conditions and widths, from five to seven lanes, and traffic counts up to 50,000 vehicles per day. Many pedestrian deaths have occurred over the years—including one in May of 2018. One of the most challenging sections is the intersection with I-290, a classic cloverleaf that uses a large acreage for ramps. This is arguably the most pedestrian-unfriendly section of the roadway, and it generates no tax revenue or economic value for the city.

The team drew a smart solution: Replace the cloverleaf with diamond-shaped ramps linked to the boulevard via roundabouts (see drawing above). This would take up a small fraction of the current intersection acreage. The boulevard would go over the highway in the proposed configuration. Borrowing a solution from Columbus, Ohio, a short highway cap would allow liner buildings on both sides of the boulevard, turning the intersection into a town center.

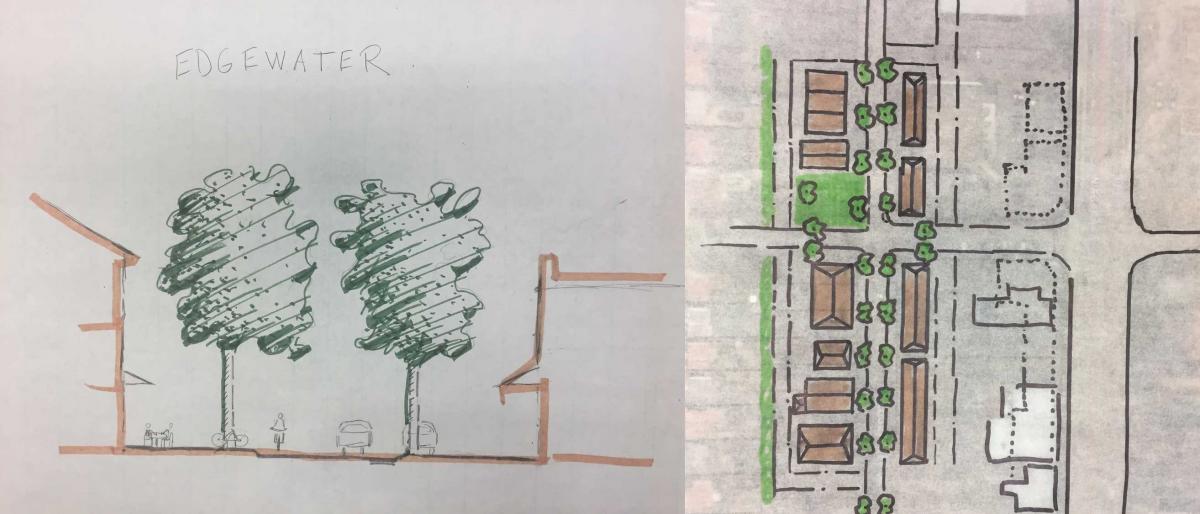

The team drew several options for converting the thoroughfare into a true boulevard (see drawing above). Proposals would make room for transit, bike-ped facilities, street trees, and on-street parking, —and the designs would slow speeds to save lives. A planned street parallel to Niagara Falls Boulevard, Edgewater Drive, currently exists as a paper-street only, with undeveloped lots. This street could be developed as a slow-moving, low-volume street that would prioritize bicycle and pedestrian traffic. Small neighborhood parks could be built. Edgewater Drive would bring more connections to the neighborhood—and better connectivity is better for pedestrians.

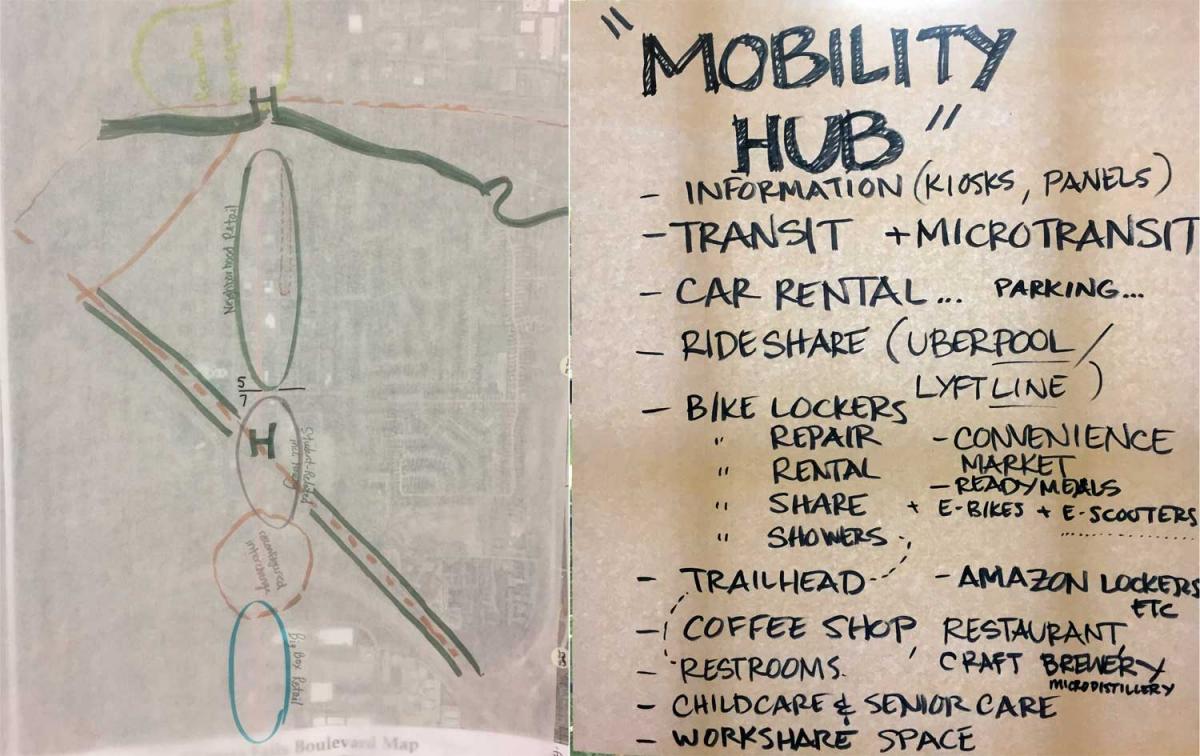

The team fleshed out the idea of "mobility hubs" along the boulevard, emphasizing multimodal activity such as transit, carshare, bicycling facilities, and gathering places like coffee shops, restaurants, and craft breweries. These mobility hubs would be destinations, in addition to offering places for people to switch from one mode to another.

Others teams drew equally impressive visions for a street retrofit at Audubon, a 1970s new town within Amherst; a mixed-use town center at the entrance of the University of Buffalo; and the best route and station sites for the transit line itself.

These ideas will no doubt change prior to implementation; Nevertheless they offer strong, common-sense planning ideas that should move the town forward in its pursuit of planning and retrofit for the next generation.