An accidental urban entertainment district

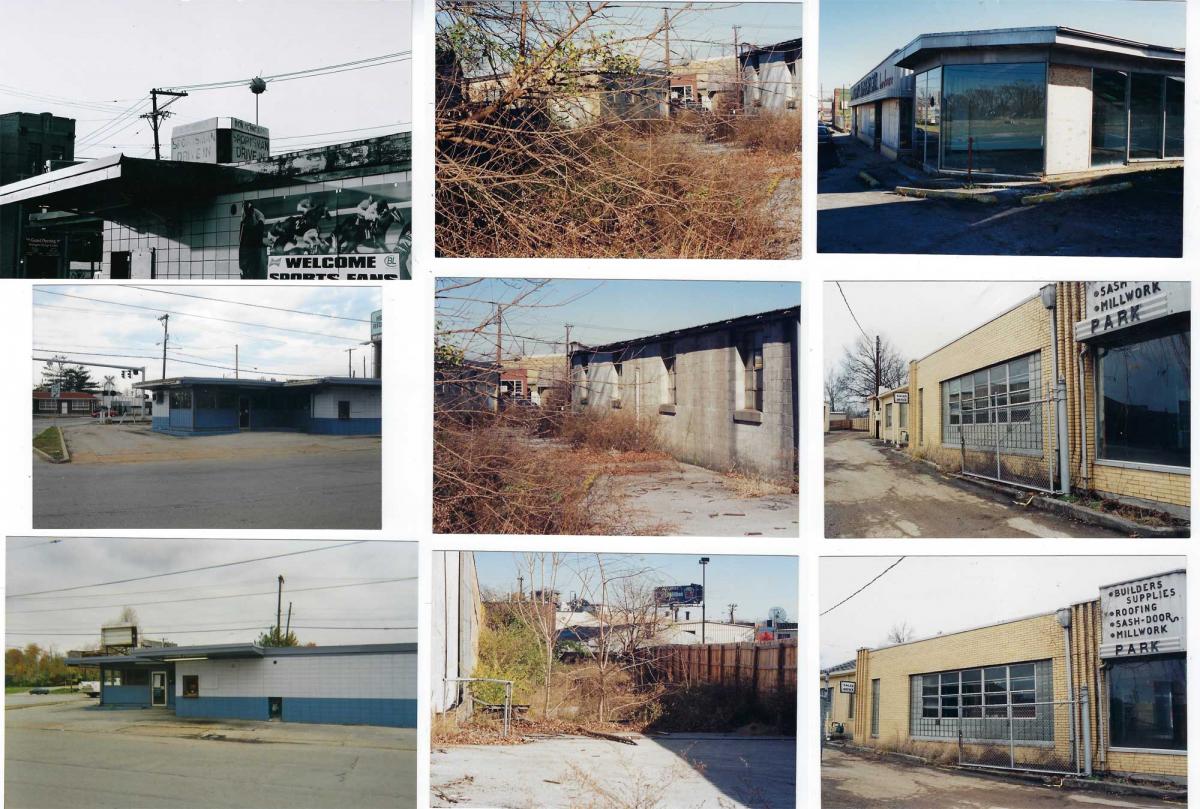

Randy Walker moved his electrical contracting business into a disinvested industrial building in Lexington, Kentucky, 40 years ago, and started buying nearby abandoned buildings and fixing them up.

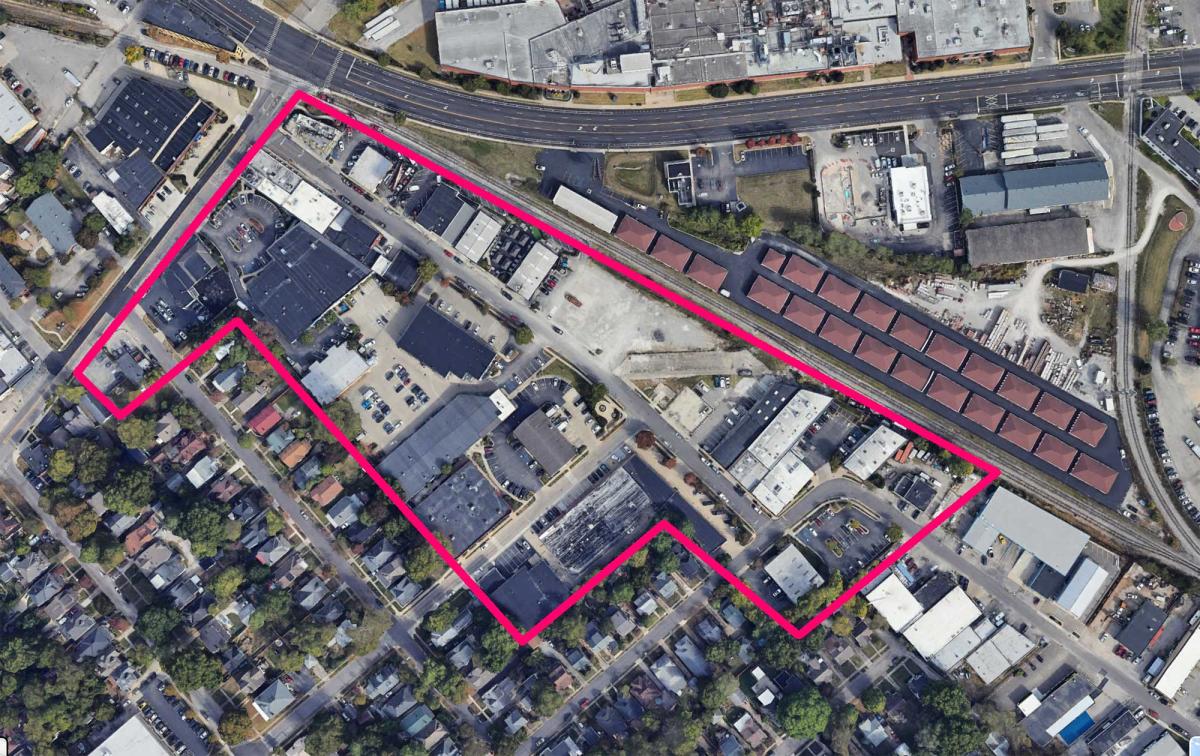

The revitalization steadily expanded into the 10-acre Warehouse Block, an urban entertainment district spanning several mixed-use blocks. Chad Walker, Randy’s son, now manages the Warehouse Block with more than 50 businesses. Included are seven eateries, a farmer’s market, businesses that specialize in games and play, fitness, retail, and services.

“This is like many restored warehouse districts, except the difference is that it wasn’t an intentional thing,” says Chad Walker, who worked for several decades on the project with his father and for many years with his brother. “We started and kept going.”

The district is very informal. It’s a mishmash of industrial, warehouse, and commercial buildings. But that doesn’t matter much, because the buildings have character and variety. The performance and event space is a former railroad loading yard, with paved parking, a large diagonal concrete pad, some unpaved ground, and landscaping.

It helps that the infrastructure is walkable. It is built on a grid that connects to three nearby residential neighborhoods. The streets are relatively narrow, with some on-street parking. There are sidewalks, a few street trees, and the buildings come close to the street. Everything is nearby.

The Warehouse Block is centered on Walton, National, and North Ashland avenues. The Walkers restored dozens of buildings to create a social center for Lexington, a city of about 330,000 people.

“We have some old historic properties, and some are a bit newer, but they have a nice blend between the properties and the tenants,” Walker says. The Bell Court, Mentelle, and Kenwick neighborhoods, with housing from the early 20th Century, connect to the district. The Walkers created this district by fixing up and reoccupying what was already there, with very little new construction. The owners have planted trees and have been enabled by a zoning overlay district adopted by the City.

If Walker has a development philosophy, it has several components. One is that he supports local agriculture by bringing produce to the City. “The idea is to bring the farm to the neighborhood”—in the form of farm-to-table and farm-to-retail. So much of the land around Lexington is devoted to horses and estates—general agriculture needs support, he says.

Because much of the real estate was bought cheaply with low debt, it helps to keep the rents low and attract local businesses. There are no chain stores. Performances are generally free and include many music genres, in addition to the more highbrow Kentucky Ballet, which is a tenant.

“This generation doesn’t like stuffy,” says Walker. “They don’t want to dress up. They want an approachability that lets you walk by and see what’s happening today. Let’s just go to the neighborhood and see what’s going on.”

He has learned to gather neighborhood input, from the design of the outdoor space to which new businesses would make locals happy. They want coffee and ice cream, which is no surprise, and they are now available. The biggest mistake was renting to a music venue, Cosmic Charlie’s, about 10 years ago. It was too loud and not appropriate for the area. It took about a year to resolve as the business found a new location.

This kind of incremental urban entertainment district, which turned an eyesore into an amenity, could be created in many places that have empty warehouses and commercial buildings. Although the result is significant for Lexington, it covers a relatively small area embedded in surrounding neighborhoods. There must be hundreds of similar places in cities and towns, large and small. Some of them have been revitalized—others await incremental development. The Warehouse Block models one way to do that.