In 2026, let’s resolve to save pedestrian lives

Pedestrian deaths are a ghoulish topic; it’s easier to avert our eyes. But they indicate that something has gone seriously wrong with planning and the public realm. Pedestrian deaths have risen steadily for a decade and a half—to 7,314 in 2023, from 4,302 in 2010. The good news is that if we care, we can do something about it.

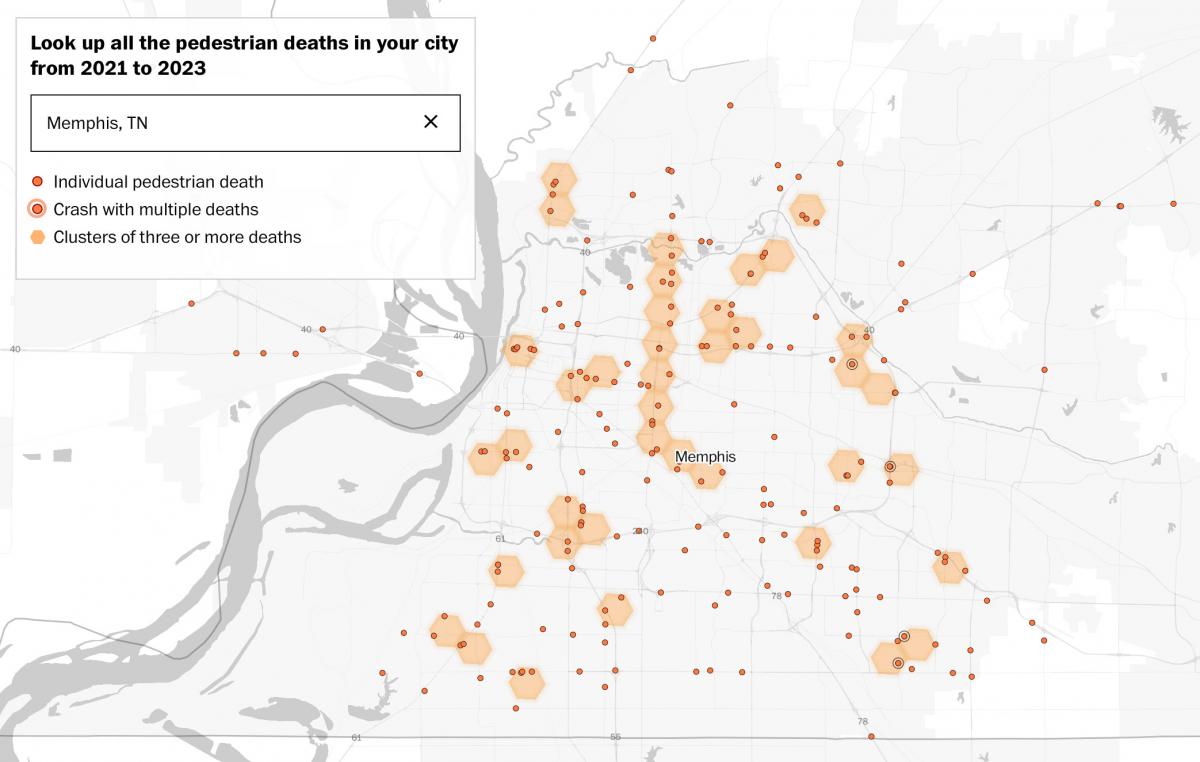

This epidemic can be located with pinpoint accuracy. And the solutions are not that expensive or exotic. These deaths are not concentrated where people walk the most. Many highly walkable neighborhoods—some of the most highly walked places on Earth, like Times Square—have few to no pedestrian deaths.

Rather, they are concentrated on particular kinds of streets, according to a recent report in The Washington Post. They are wide, multilane (typically 4-7 or more lanes), thoroughfares with fast-moving traffic.

Clusters of mortality and morbidity occur on thoroughfares that cut through economically distressed neighborhoods with fading commercial strips, the Post reports. At the same time, more residents in these areas lack cars and are forced to walk.

“Wide roads and fast-moving vehicles — especially when combined with signs of poverty, homelessness, drug and alcohol abuse, and a lack of pedestrian-focused roadway improvements — produced a pattern of death-by-vehicle that is uniquely American, according to the investigation, which draws on crash data, census records and thousands of pages of police reports, as well as interviews with current and former officials, engineering experts and victims’ families,” the Post reports.

The report found 825 locations across the US where three recent pedestrian deaths were concentrated within a mile of each other. Such locations more than tripled from 275 in 2010.

“The most dangerous areas are no longer in congested downtowns but in less dense neighborhoods toward the edges of cities, according to a study by University of New Mexico researchers. Those roads on urban outskirts were constructed decades ago to connect towns before the era of Interstate highways. As businesses and residences have sprawled around them, these arteries now feature people walking to fast-food restaurants, convenience stores, liquor stores, supermarkets and more.”

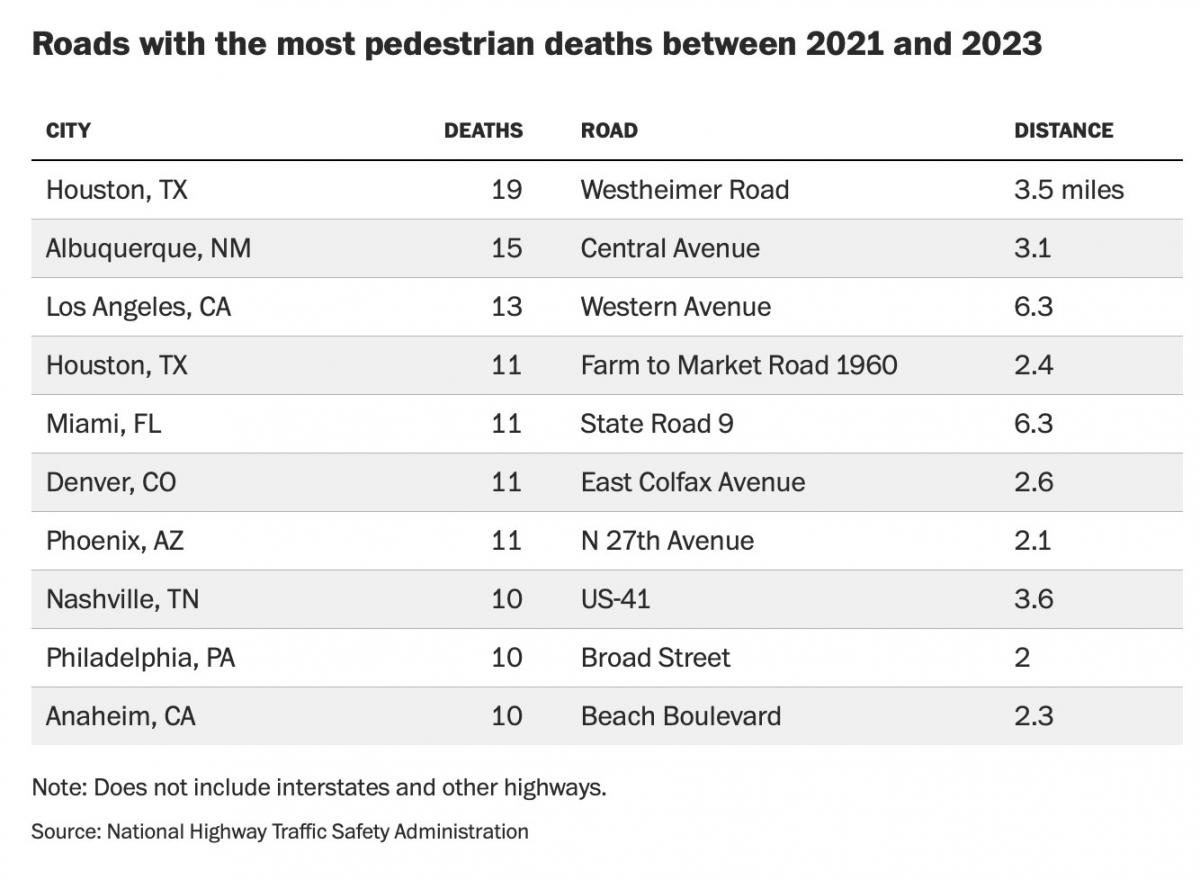

Here's a list of the most dangerous stretches of thoroughfares for pedestrians in the US (source: The Washington Post):

Let me put it another way. The US has 4.1 million miles of drivable thoroughfares. The pedestrian death zones occupy just one quarter of one one-thousandth of those miles. We know exactly where they are. Surely, we can do something about it.

The solution for these deadly places are well-known: crosswalks, pedestrian signals, bumpouts (to reduce crossing distance), street trees, roundabouts, pedestrian islands, and narrowing of lanes to slow traffic (which can be done with paint). These improvements don't have to be fancy to be effective. They are part of a toolbox that urbanists employ regularly in many kinds of locations. As the Post writes: “Even safety projects requiring construction can be relatively inexpensive. Speed humps cost around $5,000. Roundabouts, around $170,000. An overpass, around $250,000.”

Focusing on a very small segment of American thoroughfares, we can make a big difference. As a bonus for drivers, who are horrified at the thought of hitting a pedestrian, these thoroughfares are also dangerous for those in cars. Slowing traffic at key junctures would also reduce injury accidents and fatal crashes for those inside cars.

An additional positive side effect of pedestrian improvements is that they foster neighborhood pride and often boost business activity, because these are struggling commercial areas.

Why is this not a higher priority? This topic is hard to think about at any time, let alone the end of the year when we want to celebrate. But we should resolve to take action on pedestrian deaths in 2026. Saving pedestrian lives will pay for itself many times over.